Making Work From Yeoseong Gukgeuk

―That makes sense. Speaking of Korea's yeoseong gukgeuk, it ended up forgotten for decades. After that, modernization and democratization moved forward, and amidst a drastic change of eras, it was rediscovered today by you. Now it is staged again as an artwork, and performers of the day are to appear on the stage again. Was it difficult to persuade them to perform again?

siren: Before answering that question, I would like to say that I think the fact that yeoseong gukgeuk was forgotten after the '70s was the result of an intentional exclusion. From the time when Chung-hee Park's government took power at the end of the '60s, in order to hasten toward its goal of becoming a modern nation state, Korea has needed to, in Hobsbawm's terms, invent traditions. While changgeuk (Korean opera), pansori (a form of musical storytelling), and the like were designated cultural assets, male artists judged yeoseong gukgeuk to be lacking universality because it involved all-female groups, thus they excluded it, and the mixed-gender style changgeuk became a cultural asset. Because of this, the yeoseong gukgeuk people still carry with them a kind of trauma, since, in spite of flourishing so well, they suddenly fell into the theater basement. They still want to continue appearing on stage, but while they still call themselves performers even now, they can't perform. Even if they get an opportunity to perform, it's primarily on incredibly small stages or for shows opened to very specific, limited audiences. The problem is that they cannot perform to their greatest capacity as actors.

When I first invited them to make a performance work together, they declined. It was not that they were reluctant to appear on stage, but that contemporary performance, which lacks the former brilliance of their times, was not to their liking. They said they wouldn't do it unless I created a flamboyant stage like the ones from long ago. I spent a lot of energy helping them understand that contemporary art is not about showiness.

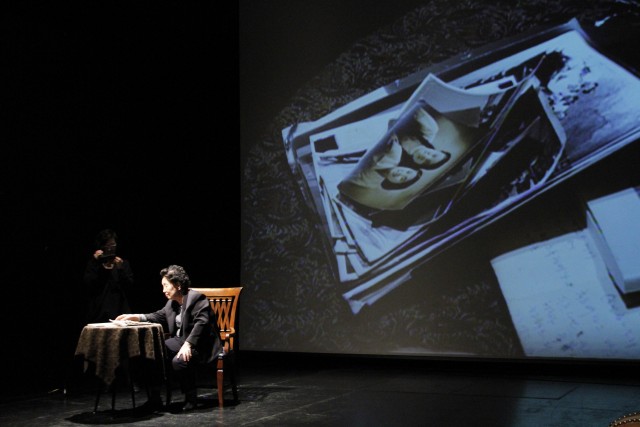

At first (Off) Stage and Masterclass were two separate pieces, and we decided to present these two together, but Young-sook Cho's performance in (Off) Stage marked a turning point. In the beginning, she scolded me, saying "What is this? It is not theater!" and rejecting it. However, I explained that I was not going to create yeoseong gukgeuk itself, but rather a performance out of her story of being a great yeoseong gukgeuk actor. In that case, it would raise her own profile as well.

She must have felt refreshed, as if she had undergone a psychotherapy session, by getting to tell her own story on stage. She must have proudly boasted to other actors about the performance, and they must have envied her or become jealous, but now other performers completely trust me and the mood seems to be one of saying that they are willing to go along as long as its with me.

―I remember that Young-sook Cho was a sammai (a supporting male role who makes comic remarks). She talked about never playing the main character. In any case, she simply looked so happy, lively, and full of confidence to be on the stage. I remember her well even now.

siren: We put small pieces together and showed it for the first time at Festival Bo:m. Ms. Cho's son and grandson came to see it. Her son said it was the best performance by his mother that he had ever seen. It seemed Ms. Cho's pride was recovered. It felt like we did psychological therapy rather than presenting a piece.

(Off)Stage/Masterclass performed at Festival Bo:m, 2013 (c)siren eun young jung

(Off)Stage/Masterclass performed at Festival Bo:m, 2013 (c)siren eun young jung

―When the yeoseong gukgeuk actor, who is performing a theatrical form that began after the end of Japanese colonial rule, performed again at Festival Bo:m and then was invited to TPAM 2014 in Yokohama, Japan, what kind of communication took place?

siren: Yeoseong gukgeuk started right after the colonial period, so there is a slight time difference, but these people experienced colonial rule, so it seems that she was of two minds about it. She wanted to go to Japan to show off how great they were, yet this was tempered by still lingering feelings of being a Japanese subject, and part of her also seemed to return to the role of the sammai again.

―What kind of feeling is this feeling of being a Japanese subject?

siren: At that time, they did not consider themselves as Korean but rather as belonging to Japan, and they wanted Japanese to see them and think of them in a good light, so it seems they still feel like they must behave carefully.

―I heard that when the percussionist was lying down in the dressing room, she cautioned him, saying "Don't do that, we are in Japan."

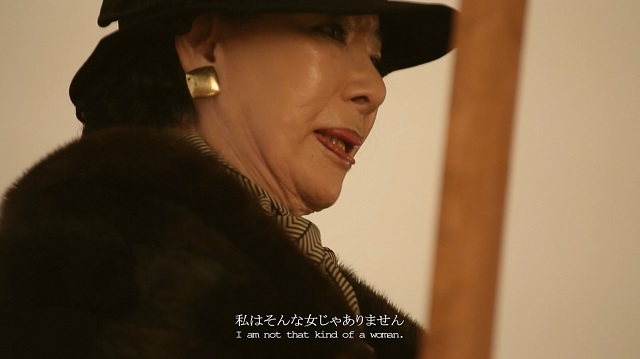

siren: Yes, that's right. The musicians were all young, so they interacted casually with Japanese people and behaved as they liked. Watching this situation, Ms. Cho worried about what the Japanese would think of them. This must have been a question of pride. After that, they felt the young people had been impolite to the Japanese. There were always these dual-layers coexisting. Another actor came for the performance I am not going to sing in the show that you also attended at Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art (the special exhibition Hiroshima Trilogy: 70th Anniversary of the Atomic Bombing, Part III: Discordant Harmony). In this exhibition, there were other Japanese and Chinese artists and curators participating. While this actor was very polite toward the Japanese, she took a haughty attitude toward the Chinese.

―I didn't realize that. That gives me mixed feelings.

I am not going to sing, Mixed media, Installation and Performance, Dimension variable, 00:16:00, 2015

(c)siren eun young jung

I am not going to sing, Mixed media, Installation and Performance, Dimension variable, 00:16:00, 2015

(c)siren eun young jung

Research on Takarazuka

―Now I would like to ask about your research on Takarazuka. During your residency in Kobe, how did you conduct your research?

siren: As it was the birthplace of the group, I looked around the city of Takarazuka: I saw shows, observed the everyday occurrences around the theaters first-hand, and interviewed people on the periphery of the Takarazuka Revue Company. As Takarazuka didn't grant me permission, I couldn't interview actors or other members of the company and music school, but I did interview fans and other related people. Additionally, since the library in the town where Ichizō Kobayashi lived had almost all of the documents concerning Takarazuka, I made frequent inquiries there. I put myself in the environment in which Takarazuka exists, and then researched it through direct observation and reviews of relevant documents.

―Did you enjoy their show?

siren: It is too interesting. It is packed full of almost every element that contemporary art has rejected, and although, like shinpa (Japanese "new school" theatrical dramas), its almost embarrassing to watch, there is something fascinating and exciting about it.

―It seems that Takarazuka performers are closely bonded to their fans, even after retirement.

siren: Yes. Yeoseong gukgeuk performers and fans, too, are exchanging correspondence even today. Even though everyone is seventy to eighty years old, the fans even argue over who is going to sit next to the actors. About once every two years, they have a public performance that is a bit bigger than usual, and at that time the fans bring food to the green room—as much food as if it were a banquet—and offer these refreshments to their favorite stars. The actors never share this food with the other performers.

Imagination and Gender On-/Off-stage

―There was a wedding photo in which a yeoseong gukgeuk star played a groom and a fan was the bride. It was a very impressive photo, and indicates how the onstage imagination and fantasy continues even offstage, or in other words, after descending from the stage. What, specifically, about the offstage gender images grabs your interest?

siren: I often add the word "offstage" to the title of a work, and when I do that, I frequently put a slash between "off" and "stage," or place "off" in parentheses. This is because I think offstage and onstage have become virtually one in the same thing in yeoseong gukgeuk. In interviewing the performers, I felt the biggest difference between them and actors in other genres—although I'm not so knowledgeable about other genres—was that the everyday lives of yeoseong gukgeuk performers always exist only for the sake of their onstage activity. In spite of the fact that they don't really have a stage to stand on anymore, they are almost absurdly prepared for one. Whenever I visit their homes, they are making costumes, although they neither know when they might wear them nor have a performance scheduled. They also take out, sew, and repair costumes from long ago. The interiors of their homes look as if they are about go out to perform tomorrow. Also, because they have to be men onstage, more than a few of them live as men even in their daily lives. And I also heard more used to do that in the old days.

(Off)Stage/Masterclass, Performance, 01:25:00, 2013 (c)siren eun young jung

―Is that about how they speak and behave, for example?

siren: For some, yes, and there are also those whose true sexuality is close to transgender, and some who have formed families as lesbians. The ways in which they reveal their masculinity in daily life vary. I think that's because they live in the ways they understand "males" ought to live. It seems that long ago many people used to be confused about, or simply couldn't judge their own sexual identities.

Although I think there wasn't a word to describe this at the time so she wasn't called this, there was a person who, no matter how you look at it, appeared absolutely transgender. She was suffering from cancer, but apparently her fans accepted her into their homes, hid her from the public, and took care of her through her last moments.

On the flip side, there were also many who lived as exceedingly ordinary housewives. Therefore, what I tried to discover in the lives of these people who switched back and forth between on- and off-stage was that gender is something that comes into view in the course of living your life. Looking into their lives, it began to appear entirely natural that gender is not something innate that you are born into, but rather that you become female or male as a result of the way you perform in daily life.

I agree, that wedding photo is shocking. They, themselves, may have only considered it as mere play, but when that photo crosses months and years to appear in front of me, what exactly does it indicate? I felt that there were countless layers of gender performance contained within it. That performer who passed away lived her whole life as a heterosexual woman, but while tackling this work, I wondered if perhaps she wasn't.

―The performance for Festival Bo:m was in 2013, right? How were the reactions of the audience?

siren: The response was really very good. Though I don't really know how they read and enjoyed the performance. In the second performance, because there were a lot of audience members from the gay community, the reactions were quite different. The audience for the first show were regular festival goers, and they all enjoyed the show.

―What were the reactions of the audience members from the gay community?

siren: It was a real uproar. In the latter half of this show an audience member is invited onto the stage, and the man who was chosen just happened to be a queer film director who is quite famous in Korea's gay community. A lot of his friends were also in the audience. It felt as if they had finally found a kind of entertainment they could really enjoy. While I think there were those in the audience who didn't notice the complexity hidden between the accumulated layers of lines, the members of the gay community must have been able to see it quite clearly. The yeoseong gukgeuk performer Deung-woo Lee would first give an explanation and demonstrate how to play a male character, then beckon an audience member onstage to teach him or her the basics, but everyone started to imitate what he was doing onstage.

Seong-hee Kim, the artistic director of Festival Bo:m at that time, said that simply by dint of the fact that it drew a great crowd of new spectators unseen at her festival before, it should already be considered a big success. Also, Korean audiences are very direct. Japanese audiences are quite obedient. The gay audience in Korea all imitated what was shown on stage as if everyone was being coached directly by the teacher.

(Off)Stage/Masterclass, Performance, 01:25:00, 2013 (c)siren eun young jung

Research in Tokyo and the Politics of Style

―I understand that after this you are going to stay in Tokyo for one month to continue your research on Takarazuka, but what kind of research will you do in Tokyo?

siren:

I have visited the Tokyo Takarazuka Theater many times. Fans in Tokyo are more visibly positive and supportive. While some of the fans in Kobe move meekly, a real crowd of fans are moving here, and passersby watch the spectacle of these fans' movements. It was so interesting that I stayed there watching for a long time. The generations of the audiences differ too. I intend to continue interviewing and observing while participating here, too, but more so than would be possible staying for a month in Kobe, with just a few days in Tokyo I have a feeling I've already been able to better see the enthusiasm of the core followers.

In watching Takarazuka, I thought that a significant difference from yeoseong gukgeuk would be Takarazuka's complete stylization. I am intrigued by style, so I think I would like to try viewing various styles of theater besides Takarazuka. For example, classical theater. There are more chances to see those kinds of shows in Tokyo, so I want to try watching anything from taishū engeki (lit. "popular theater") to strip shows. I want to see and compare prototypically Japanese theatrical styles.

―So you also have an interest in style. Is that because you are of a mind that there is something important in style itself?

siren: Yes, of course. Yeoseong gukgeuk emphasized theatricality over style, but I suppose Takarazuka started with style. Prototypical style in and of itself is important in other Japanese performing arts that are known to foreigners, as well. The subject matter of kabuki or bunraku is very anti-feminist and boring, but I was able to find some point of interest and see them because they were packed so full of stylistic elements.

―I think that when artistic formality dominates, there is a tendency for simply fulfilling the stylistic requirements to become the main focus, and thus elements that make us reflect directly on the current situation of our own society and world today become few and far between, but what do you think?

siren: During my research, I interviewed a performer of Taiwanese opera. She said that, for her, Taiwanese opera was fascinating because she felt it was more connected to everyday life than other traditional performing arts. On the other hand, for someone like me who doesn't understand the words and can't comprehend the content at all, the classical styles were more comprehensible and charming. Apparently performers and audience members each find different elements fascinating, as might be expected since the former live inside of it, and latter are on the outside.

And, although it is totally detached from everyday life, I don't think style erases the quotidian or the social and political reality inside everyday life. Recently I have become more interested in what can be done through style. Isn't it possible that a style in and of itself might be even more political or social? When we look at art, we have a tendency to fixate on its contents, but I wonder if that is enough? Of course, I don't mean to say that kabuki is political, but I would like take a look at the stories and other elements through the style kabuki has conserved. That might be a good approach for someone like me who doesn't understand Japanese at all.

Photo: Jouji Suzuki

The Potential of Performing Arts

―Unlike fine art or moving images, performing arts including theater, performance, and dance are live. If you are not there at that time when it happens, you cannot see it or engage with it. As a visual artist, why do you deal with works for the stage? And why, even if they have different styles and backgrounds, do you follow various all-female forms of performing arts? Also, what do you think of femininity in relation to the reality of being a woman in the performing arts?

siren:

I don't intend to explore femininity through my work. On the contrary, I have long been interested in how the designation of "woman" is assigned and how one is given instruction and influenced by being a woman. So, I empathize greatly with the American gender theorist Judith Butler's notion "Gender performativity," and thus the genre called performance is both a great challenge and a solution for me.

It was difficult when I moved from moving images and fine art to performing arts. I was really worried about not being able to control everything myself, but by the same token, the fact that through surviving on stage a different meaning is produced has, itself, become a great stimulus for me.

The female roles reproduced in the media, including stage and television, are almost entirely identical. But you can have a real 80-year-old woman stand on stage, for example. I find it appealing that this world of performing arts is a world in which that is possible. In moving image media, it is easy to shoot an old woman, and you can just cut any scenes that aren't smooth to finish it off. However, when an 80-year-old woman stands on stage, no matter whether her back is bent, her manner of speech is hard to follow, or she forgets her lines, there is a world that is established to which the audience reacts. Surely that is precisely a gender that is performed, a gender that ages, and a gender that cannot be defined, and I think its continued survival is the magic of the stage.

I think that performing arts, especially, are the best art form for people with non-normative genders to reveal themselves. I suppose that is why things like drag shows or transgender shows still exist. Working in the field, I have become more and more interested in that aspect of performing arts.

Moving forward, I won't only be working with the old women of yeoseong gukgeuk; I'm also preparing works with other kinds of people. However, there is no change in my desire to continue using the form of performing arts, and the kind of magic that the stage delivers.

―Expression in performance arouses some kinds of questions, doesn't it.

siren: Yes, and something unexpected always happens, and because of it you end up thinking of the next step. Very refined ideas and aesthetics end up dominating in the art world. Although there are profound expressions to be found, the idea of the community that forms between people tends to be forgotten. Stage performance assigns me the role of coordinating and resolving differences between people, so I learn a lot from it.

―Now I think I understand why you shifted to performing arts. Are you not going to present (Off) Stage / Masterclass again?

siren: It seems it is very hard for the over 80 years old performer to travel a long way to perform publicly. When I suggest it to them, they aren't very pleased. There was talk of staging (Off) Stage / Masterclass in France this year for the 130th anniversary of the Korea–France Treaty of Friendship, but she said that going even farther than Japan would be impossible.

―I hope that your research on Takarazuka will go smoothly, and look forward to your future activities. Thank you very much for your time today.

Photo: Jouji Suzuki

(February 14, 2016 at BankART Studio NYK)

Interview and text:Makiko Yamaguchi

After working on cultural exchange between Japan and Germany through music, theater, dance, and photography in the Cultural Department at the Goethe-Institut Tokyo, she managed performing arts exchanges, the promotion of Japanese culture, and information exchanges at the Japanese Culture Institute in Cologne (The Japan Foundation). From spring 2011, as Director at the Tokyo Culture Creation Project Office of the Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture, she was in charge of the networking program. Currently she works at The Japan Foundation Asia Center.

Translation:Jooyoung Koh