Shogo Ohta's "The Water Station"

Uchino: Okay that's really interesting.

You are an admirer of Ohta Shogo's work and you finally brought your version of The Water Station to the Kyoto Experiment 2 years ago and how did you come up with it?

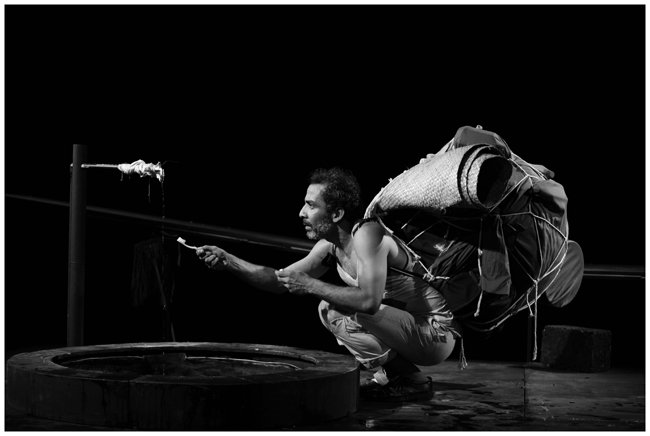

Photo: Deljo Thekkekkara

Sankar: I kind of knew about this play during my training in Singapore. Phillip Zarrilli*13 had directed a piece so that's the first time I came across this play. I was not part of it. When I came to Delhi, I was looking at texts without speech. So Ohta Shogo was something, which was a big part of puzzle and intrigue for me. Incidentally, I met Ando Tomoko, an original member of The Water Station in Delhi when she came to perform Kiosk, which came to the National Theater Festival.

*13 Phillip Zarrilli (1947- ) is a U.S. researcher, practitioner and director specializing in the Indian traditional theater. While teaching at British and American universities, he has resided in Kerala to master the techniques of Indian traditional theater and martial arts. His creative work as well as his research and educational activities are based on his experiences in Kerala.

Uchino: Okay.

Sankar: I was reading this text. And, I kind of knew bits and pieces and nooks and corners of the text, and the play, the Mari Boyd translation says GIRL: Ando Tomoko and then the text starts. The girl in dim light comes walking... I saw the program of the festival and there was this Ando Tomoko. So, I wondered if it is this the same person? Maybe yes, maybe no. So, I got in touch with her, wrote a mail and asked and she said yes. So, I organized a meeting with her which led into a workshop. She came to Kerala and gave us a workshop and then that sort of started to realize The Water Station production in Thrissur. We traveled around in India extensively. Then on the occasion of Ohta's 10th anniversary, it was recreated and brought to Kyoto by Kyoto University of Art and Design.

Photo: Shoeb Mashadi

Uchino: I found your "Water Station" very interesting in the sense that I kept thinking that Ohta had an ideological problem with it. When the Japanese people, by which I mean those whose native language happens to be Japanese, when they fell in silence, it may mean that there is kind of shared essentialist sentiments that "we all are the Japanese." So, there is a very dangerous trap of nationalism and parochialism there. And, Ohta was very aware of that. He was trying to do something else when he was creating Sand Station in later years. He did a workshop in Berlin. He was trying to incorporate these different kinds of bodies, which did work.

I liked your work very much because it seemed to transform Ohta's work into a very different one, which Ohta would have appreciated very much because he really wanted to do that but he really didn't know how.

Sankar: In the context of India, for us, the silence comes out of this difference that we have, not because of something, which holds us together but something which keeps us apart. Like, we have 24 languages, plus a thousand not officially recognized languages, and all the actors they speak different languages as they are from different places of India. Then, there is no language. There is no commonality and what is common is only silence and it doesn't go into nationalism.

Uchino: Yes exactly!

photo: Yuki Moriya

Sankar: And, it's not a monolingual cast of actors. It's really like multilingual and it's very difficult for us to speak together. Either we have to speak in English, most don't and the rest and our English are all very different English or there is Hindi, which we don't like. And, I remember this one thing, which you brought up, which kept thinking me even after this Kyoto. I think Ohta was more fundamental. It's more basic.

Uchino: Yeah, okay. But "essentially human" is a very tricky notion. I think Ohta knew that very well. I had a lot of discussion with him later in his life. That's one of the reasons why he kind of quit actually creating a work with professional actors. He didn't really know how to proceed from there. So, he went to the university and he was teaching the students but not really trying to create something with the professional actors because he was afraid of becoming monolithic, very nationalistic, I mean essentialist and it was quite difficult to get the renewed sense of universality to the work.

Two extra questions. About your theater in the jungle, you used energy there or is electricity there, water supply?

Sankar: Yes. We have a single-phase electricity connection from the government but now slowly I'm making it solar, making it a renewable resource. We have a well from where we draw water now.

Uchino: So, you have to take the water from the well.

Sankar: Yes. and also we have access to the river.

Uchino: And you grow the vegetables or you buy the grocery?

Sankar: I grow coffee, pepper, cashew nuts, banana, cardamon, mango, coconut, many things grow. , I also buy groceries. Like 2 kilometers away there is a shop and whenever you go down the mountain, you stock up things. We're trying to be as much as possible to be off the grid.

Uchino: You're not getting any money from the government? Any funding?

Sankar: Not from Indian government. But I have been supported by the Norwegian, the Teater Ibsen, for one of my projects there. It's called Tribal Ibsen Project...

Uchino: That's interesting.

Sankar: ...which helped me to travel around the region, meet people, work and live there. I have created a few theatre pieces with the communities here, young and old, and we traveled as far as to Bombay. These kinds of works have been supported by the Ibsen scholarships. Apart from that I work in Munich, I work in Europe, I use that money to make the theatre space.

Uchino: Yeah. Putting everything in there. I hear your work is coming to Japan in January 2019.

Sankar: Yes.

Criminal Tribes Act.

Uchino: What is it?

Sankar: It is a British legislation. As an act of the law, as a legislation, 1871, the British started to enact a series of legislations. Suddenly, 1857, the first independence movement, the rebellion started and that's when the British realized that there is this whole other India now. They were dealing with the feudal affluent privileged. And, in their eyes these were the only people but then when this big push from the fringes came that's when the British realized there is this other India now they have to deal with. So, they started to enact a series of legislation and in 1871, they brought this Criminal Tribes Act. The assumption of this act is that in India, there are castes, so every community, there is a carpenter community, there is a goldsmith community, there is a tree woodcutter community.

They also assumed that there must be also a caste for criminals. They notified around 150 tribes, communities as criminals. And, when they talked about criminals, they said they were criminals from time immemorial because they are destined to be criminals by the usage of caste. And, the only way to sort of stop this is to eradicate them. So in order to profile, label, and segregate these communities, they enacted this Criminal Tribes Act, and the social stigma and ostracism continues right up to this very day.

Uchino: That's kind of a British conspiracy to consolidate the caste system, right? They intentionally did that.

Sankar: It could easily sit well with this Hindu structure, which is how the centuries old hierarchies and caste system got legalized, legitimized. You could be a born criminal if you are born into that community.

Uchino: The work is with your actors?

Sankar: Yeah. Two of my actors, both who are playing in The Water Station. One is from Karnataka, Chandru, and the other actor from Delhi, Anirudh. So, Anirudh played the husband, and Chandru played the man through the couple scenes. And then, I got this proposal from Sandro Lunin from the Zurich Theater Spektakel asking me will you be interested to create something short and easily travelable? So I said, yeah why not. And then, these two actors were the most trusted actors. And, I was also looking at history of this construct of what is tribe and from where does it come from and then I come into this legislation. So, I called these two actors and told them that we have this proposal, and I am interested to work on this legislation, so would you like to come so it can start. And, we don't have a common language. So Chandru speaks Kannada, Rudi (Anirudh) speaks English. I speak English. I speak bits and pieces of Kannada. So from there, we started to discuss and device and we created this 30-minute piece.

Uchino: Premiered in Zurich?

Sankar: Premiered in Zurich. Then we took it to Munich. We showed it in Bombay last month.

Uchino: For the festival or independently?

Sankar: Munich was for Spielart festival. The Bombay show was an independent event organized by a theatre group there. We started as a 25-minute piece, which became 30, which became 35, now around 38 minutes, I hope to develop further.

Uchino: Thank you very much. I am looking forward to seeing your work in Japan.

Sankar: Thank you.

[On Febrary 10, 2018 at the BankART Studio NYK library]

More Information

Performance information at the festival / Theaterfestival SPIELART Munchen (November 2017)

Ciriminal Tribes Act will be performed in January 2019 in Kyoto and Tokyo as follows:

Kyoto

- Date & Time: Sun. 13 January 2019, 3:00 p.m.

Mon. 14 January 2019, 3:00 p.m. - Venue: Kyoto University of Art and Design / Interdisciplinary Research Center for Performing Arts

- Organize by: Kyoto University of Art and Design / Interdisciplinary Research Center for Performing Arts

- Inquires: Kyoto Performing Arts Center, Kyoto University of Art and Design

TEL: 075-791-9437

Tokyo

- Date & Time: Sat. 19 January 2019, 3:00 p.m.

Sun. 20 January 2019, 1:00 p.m. - Venue: Minato Gender Equality Center "Libra", Libra Hall

- Inquires: Theater Commons Tokyo Executive Committee

URL: http://theatercommons.tokyo/

E-mail: artscommons.tokyo.inquiry@gmail.com

Interviewer: Tadashi Uchino

Tadashi Uchino is a leading performance studies scholar, whose border-crossing research and thinking has been critically acclaimed in various interdisciplinary quarters of academics, artists and activists. He was professor of Performance Studies at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (1992-2017) in University of Tokyo and now professor of Performance Studies at Gakushuin Women’s College. His publications include: The Melodramatic Revenge: Theatre of the Private in the 1980s (1996); From Melodrama to Performance: The Twentieth Century American Theatre (2001); Crucible Bodies: Postwar Japanese Performance from Brecht to the New Millennium (2009) and The Location of J Theatre: Towards Transnational Mobilities (2016). He is currently a contributing editor for TDR, a member of board of directors for Kanagawa Arts Foundation, the Saison Foundation and Arts Council Tokyo, and of selection committee for Fukuoka Asian Culture Prize and a member of ZUNI Icosahedron’s Artistic Advisory Committee.

Interview photo: Naoaki Yamamoto