"Theater Practice", "Camino de Ansan": a project with the surviving families of the Sewol ferry disaster

Ogura: Could you tell us about your recent project with the surviving mothers of the Sewol ferry disaster?

Koh: I create a piece each year as part of a project called "Theater Practice", which I proposed myself in 2018. In 2018 I presented a piece called Directing Practice - Three Bears with an artist called Seyoung Jeong. Having graduated from a dance and performing arts school in France, he is the type of artist that you would not really have a name for in Korea. Sometimes he would be called a performance artist or he would be invited by the dance community as a choreographer. I think that this is only because he graduated from a dance school even though he has not done anything that you would call choreography. As far as I see it, what he is doing is unmistakably theatre from start to finish. But why does nobody accept that it is theatre? So the first phase was for him to practise directing a play within a project called "Theater Practice".

(C) popcon, Theater Practice Project

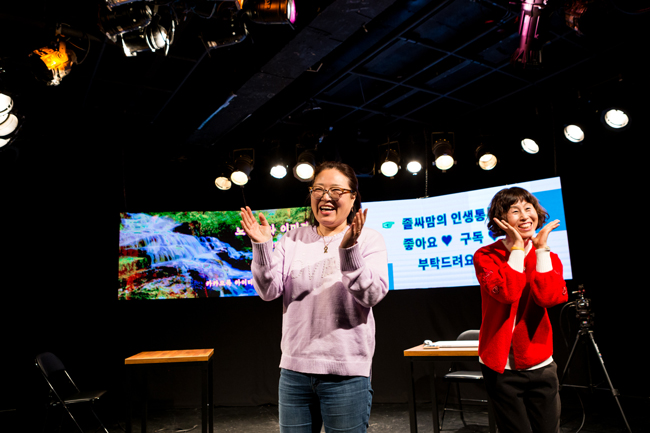

The second phase in "Theater Practice" was Acting Practice – Performing Person. What is acting and what does it mean to be an actor? These were the questions that inspired this project. So I selected two surviving mothers from the Sewol ferry disaster to be the actors. Instead of making these mothers act, I asked them what they wanted to do before they died. The planned content of this project, Acting Practice, was to make one of their wishes come true. According to my plan, this very process would become the performance, and the acting would consist of the mothers actually realising their dreams on stage. One of the mothers wanted to be a YouTuber, and the other one wanted to be a singing teacher. A singing teacher is someone who entertains everyone at a place where people gather, letting them sing together.

Ogura: What type of songs?

Koh: Traditional-style, popular songs. There are singing classes that ordinary people can take part in. You show them how to sing and create a place where people get together, sing and enjoy themselves. You could say that it is like being a recreation teacher. In Korea it is a profession. So the two mothers were able to make their dreams come true.

Ogura: When you say that they made their dreams come true, do you mean that she is now really working as a singing teacher? Is the other person active as a YouTuber?

Koh: You need a license to become a singing teacher. First this mother took lessons from a specialist and bought the necessary equipment and mobile speakers to prepare for the performance. Then we asked her to teach the songs to the audience on stage, who would have fun singing with some dance moves. After spending a month on stage, she actually obtained her license. From March she plans to have a class of her own. As for the YouTuber, the mother learned from a specialist how to film and edit videos, organise the content and prepare herself mentally as a YouTuber before actually opening her own YouTube channel three days before the first day of the performance. On stage, one video, which had been uploaded before the performance, was introduced. The mother then discussed and decided with her audience what the content of her second video would be after which she edited and uploaded the finished work on the spot.

Ogura: They are both amazing.

Koh: In our preliminary publicity, we kept it a secret that the performers would be mothers of the Sewol ferry disaster. In our advertisements you would see portraits of two very ordinary women, who in this project would "do what they wanted to do." Even during the performance, we did not say directly that they were surviving families of the Sewol disaster. The entire process that the mothers experienced in order to learn how to sing or create a YouTube video had been filmed, and this was where the incident would inevitably be brought up. When the mother was asked why she wanted to become a YouTuber, she talked about the Sewol ferry. For example she said, "People said things about me because I wasn't the student's real parent but became the stepmother after remarrying." From conversations like this, the audience could guess that the mothers were the surviving families of the Sewol ferry disaster. By seeing the performance through this layer, I thought that the audience would be left with an impression of some sort. So the process of creating the performance was also very enjoyable.

(C) Tae Yang PARK (Botong Photography)

Ogura: Who is the director?

Koh: It is Eun young Kwon, who has been invited to TPAM this year.

Ogura: Was there anything else that the mothers wanted to do?

Koh: When we actually started, there were too many things that the mothers wanted to do, so it took a long time to decide what it was that they really wanted. The mother who became a YouTuber said that she wanted to write, to publish a book. She said that she wanted to write about her daughter that she had not given birth to, a story about the conversations with her. Or the mother who became a singing teacher told us that she wanted to be a singer, a rapper and publish an album. From there, the mothers considered their options realistically and decided that what they were able to and wanted to do at that moment was to become a singing teacher and a YouTuber. From there, both mothers took lessons from specialists for about six weeks, and without even rehearsing, we structured the performance after entering the theater. I do think that rehearsing makes the performance appear false, so as an experiment to try to make it as sincere and authentic as possible, I asked for the performance to go ahead without a script even though the director told me that it was about time we had a script.

Ogura: When you launched the project, "Theater Practice", was your attention focused on rebelling against existing theatre?

Koh: Yes. I thought that the scope of what was accepted as "theatre" was a little too narrow, so I thought that I would like to broaden the concept of "theatre." I started this project in order to bring to people's attention that work like this, which until now has not been considered as a target of criticism, is indeed also "theatre." Also, I believe that it was from around this time that I started thinking that I did not want to lie on stage. I am constantly thinking what I can do to create work that is honest, but the first work, Directing Practice – Three Bears, ended up being a piece that declares that all theatre is full of lies. I had two aims, two personal goals: I wanted to both broaden the scope of theatre and create performances that were honest.

Ogura: I believe that the project, "Camino de Ansan", which continued from 2015 to 2019 for five years, has had an influence on the work that you created together with the mothers of the Sewol ferry disaster. I heard that it was through this project that you met the people who performed in Acting Practice. The Sewol ferry disaster, which was the reason why "Camino de Ansan" began in the first place, has of course received a lot of media coverage in Japan as well, and for the people of Korea it has left behind a huge social issue to deal with.

Koh: It has become a national trauma. I talked before about one of Sakaguchi Kyohei's projects being cancelled because of the Sewol ferry disaster. The festival where we were planning to present that project was the "Ansan Street Arts Festival". Ansan became the city where 250 high school students lost their lives. This outdoor festival was cancelled and was held again in May the following year. However, after the accident the city, Ansan, changed, and I thought that if I wanted to do something here I would not be able to ignore the Sewol incident. I consulted with Hansol Yoon and others with whom I had been working at the time, and we decided to walk. Not just for an hour or so but for as long as we felt pain in our feet. We thought that that was the least we could do. This is how our six-hour walking project, "Camino de Ansan", came about.

Ogura: What was the distance that you covered in this walk?

Koh: About 12 to 15 kilometres. It is a little different each year.

Ogura: Last year I walked with you. From Japan, Akumanoshirushi: "Carry-In-Project" participated. What left an impression on me was the fact that various people came together, such as the surviving families, theatre-related people and those that you were involved with in other projects. Have you been doing it every year since 2015?

Koh: Yes, it is held in May each year. For the first four years, the project was commissioned by the outdoor festival, so it was held whenever the festival took place. The content and the directors that participate are different each year. The first year, anger was the only emotion that we felt, and we were wondering where we could possibly direct this anger. You could say that Ansan is a planned city that has been built from scratch by the government, so the piece was created based on our belief that how the city had been formed was what led to the Sewol incident and that disaster was inevitable. At the time, we could not talk about this project to the surviving families, let alone approach them in any way. We did not want to suddenly appear in front of the parents and tell them that we understood their feelings, so at first we agreed to work on our own to think about the problem and create something based on our thoughts. Since then, so much has happened under the Park Geun-hye government, and there have been political and social changes in Korea. With time our memory is fading as well. Reflecting all these factors, the theme changes every year. Depending on the theme, the walking route changes as well. From around the third year, some surviving families began sending messages to support us, and we started to develop a relationship. In the fifth year, we were finally able to receive support from the organisation of surviving families, and we saw participation from several surviving families. It was owing to this relationship that we were able to realise the project, Acting Practice, which we talked about just now. We could not have suddenly approached them as strangers, explaining our project and asking them to participate. It was "Camino de Ansan" that provided the connection and brought us all the way here.

Ogura: Last year when I participated, it was not really a tour performance but mainly walking.

Koh: The first year, I was the one to curate the project, and many artists came together. From the dramatic arts, we were lucky to have participation from two theatre companies, Hansol Yoon from greenpig and Minjung Kim from Movement Dang-Dang. Minjung Kim, who is both a choreographer and a director, created the default such as the formation for walking as a group and the position of the actors. There were also three groups from the visual arts as well as literary scholars. The project started off on a large scale, where participants walked for five to six hours while some sort of performance was taking place continuously, but each year there were fewer artists participating, so we shifted our focus on walking. Whatever we did, the core of the project was for all of us to walk together for as long as possible and to share the hardship, so I think that what we did was right.

Ogura: As we were all walking together, there were a few people that drew my attention. I do not understand Korean, so I was not sure what they were talking about during the break. As we continued to walk, I realised that they were the surviving families. I noticed something among these people, a much stronger feeling that was different from mine.

Koh: What we were aiming at was to become a community as we walked together, to look at one another, to see the same scenery individually and yet have completely different feelings about it. These were the thoughts that were in my mind. I believe that walking together as a group is an important point that you cannot abandon in this project.

(C) Sang Hyuk Park, The Collective for Camino de Ansan

(C) Sang Hyuk Park, The Collective for Camino de Ansan