Part2: Chandralekha's Thoughts and Padmini Chettur's Works

I met Chandralekha in 1990 when I was 20 years old. Up to this point I had an education in classical Indian dance but never thought about a career being a performer. Went onto university, and when I was 20, I came back to Chennai. I had missed those years before when Chandra was just starting to do her research involving other dancers in the city. But when I came back to the city to do my thesis after university, I met her, and a fellow-dancer invited me to rehearsal. When I met Chandra, I knew that this would be my future somewhere. She convinced me very quickly. If I want to look back to think what it was about that moment, and about her, that turned me from a scientist back into a dancer, I think it was that I felt a need to understand history in a way that I felt Chandra could not only teach me and tell me, but show me and help me to understand in the body.

To use a term that's bandied about quite a lot, perhaps that was my moment of decolonizing. I don't know. I'm saying this with a question mark. But I'm saying this also because I know, having grown up in the '70s in India, educated in English in schooling which I know was set up by the British, until that point when I met Chandra, I hadn't questioned any of this. Most of my family were academics, and a lot of them living in the West already. I had never thought really very deeply about even, as Chandra would scathingly say to me, "You English-educated people. Even the shape of your mouth is wrong," she would tell us.

Actually, when I started to work with Chandra, dance was a very small part of the education. There were so many conversations about everything. What it meant to live in society. What it meant to be a young girl. And she would just throw these statements to us, "Don't waste your time being young and pretty. Just be ancient as quickly as you can." I understand what that is now, being well on my way to being ancient. But then, I mean, as a girl of 20 and 21, we still wanted to go to the parties and live this kind of west inspired urbanised life. There was always a conflict and a tension, but in a very loving kind of way, and the doors of her house were always open to the dancers. We were only allowed to call her Chandra, never teacher, guru, nothing like this. And there was a lot of arguing also, a lot of tension, friction... Often I've been in the span of ten years thrown out of the company several times, then invited, because she also luckily had a generosity, so she would then one month later, "OK. Come back. All is forgiven."

This was a place which was much more for me than dance school, or a choreographic center. It was the place where somehow the foundation of a certain way of thinking about dance in relation to the politics of the time was established. But having said this, three years into my work with Chandra, me being somebody who's very fond of provoking and asking questions, I started to ask questions too. There were things about the presence that I was asked to deliver in terms of Chandra's work that started to trouble me a little bit. I felt in a certain way an overwhelming sense of being a body in order to deliver an image. I felt that there was some distance between the inner life of myself, the person, the dancer, the thinker, and this portrayal of iconographic imagery that was so prevalent in her practice that I didn't believe somehow. It didn't mean that I wanted to run away from the work, no, but there was a moment of around seven years, between when I was 23 to 30, when I said, "No. I stay with Chandra. I follow her because I really need this. But I need something else. I need to start the looking for something else. "While I agreed with Chandra on the need to keep sentimentality out of dance, I still felt there could be a way to allow for a softer, more human, imperfect side of the dancer to find space within form. And, I was very keen to explore imagery and movement ideas that strayed further away from the geometric precision that she proposed.

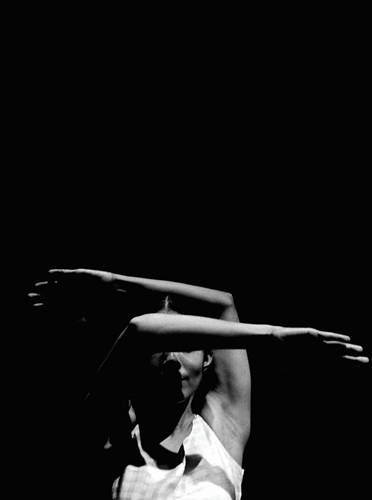

And so, after seven years of doing very small, very bad solos, small just study pieces with some of my colleagues, I made this quartet with this image, a very old image, you see, and the piece was called Fragility. I think what I'd been doing in those seven years was thinking about what were the layers of stylisation that my body had that were inherent to that many years of working in the classical dance, and with Chandralekha. It seemed as though the aesthetics of this stylisation had become a limitation, much in the same way as Bharatanatyam itself was for Chandra. Together with my colleague, Krishna Devanandan, we were for seven years just working in a studio looking at each other, watching, and trying to dismantle, and get rid of all of these layers of mannerisms. Just ways of using the hands, ways of working with the spine. Because after a certain number of years with Chandra, I also found there was an unhealthiness to some of the physicality that she was proposing that I felt was starting to create damage to my own body. Especially some of the work with the spine, but I'm not going into great technical details, but we can maybe do that in the questions.

Together with Krishna we tried to actually have conversations with practitioners from other more somatic practices, reading books, trying to look at anatomy, whatever resources. Those days, of course, there was no Internet, so whatever resources we could find. Just studying and looking. We thought to ourselves, "Is it actually possible to remove all of this knowledge and come to a point where then that knowledge could be a choice rather than pre-imposed?"

That was the idea with which I began my own physical research. Another thing that was important for me was that out of all of this research I wanted to create a pedagogy for classically trained dancers who wanted to do another kind of work. I'm not calling it contemporary or not-contemporary, but just another kind of work with the body. Fragility was for me a quartet with four women dancers where I was really interested in the question around uncertainty. Somewhere I needed to make a very concrete step away from the images of power and beauty and certainty that were replete in Chandra's work. I wanted to propose an aesthetic which was asking a question, "What happens to a classically trained dancer in a moment where they're not really sure how to do it any more?"

With Fragility somehow I came to the attention of Sasha Waltz, who was traveling in India at the time. Through her early offer of coproduction and her kind introduction of my work to other European houses, the work started to tour a little in Europe. It was the first moment when the whole idea of the machinery that surrounds this kind of work became apparent to me, what it meant to work in well-equipped theaters, the fact that the technicians that I was working with in India couldn't really cope in those kinds of contexts. It was a very confronting moment for me this time. But also a very productive one....a time when a lot of debate and discussion between young avant-garde choreographers in Europe and myself were possible through the presence of festivals like Springdance (Direction Simon Dove).The questions around nationalism, identity, aesthetics and costumes were really alive. Between that year 2000 and 2005, I made, after Fragility, a series of solos and in 2005 I made a work called Paperdoll (a result of a 3 year process), which was a co-production, a big co-production with the Schaubühne am Lehniner Platz, Théâtre de La Ville, I think, even Kunstenfestival and Springdance, Utrecht.

It was a very specific time in my career because I naively thought in this moment that I had somehow achieved a position where all of the very problematic kind of orientalist lenses that surrounded the viewing of Chandra's work somehow would go crashing away, and that this was a new moment for contemporary dance from India. There were a lot of conversations around that time with these early presenters of my work that were really looking at this terminology. What do we call this form now? Where do we present it? Do we always still present it under the banner of India itself? Do we present it with the terminology 'Contemporary Indian dance'? 'Contemporary dance from India'? And also to think a little bit about, "What do the audience need to read this very specific work and aesthetic?" How do we contextualise this?

I'm going to show a clip from Paperdoll. I'm showing the opening of the work for a specific reason—it represents very clearly my early work on developing vocabulary that still retained a stylistic nature, yet that was actually derived by asking a set of anatomical questions rather than a reiteration of traditional material. Through the other works, Fragility, and the solos, it became apparent to the people who are presenting the work that this was challenging, and it remains until this day. This difficulty in the receiving of the work was partly due to the often uncompromising temporality of the work. The fact that the dancers weren't really trying to entertain. But also the fact that there was an unfamiliarity in the language of the body, a non-connectedness to the popular Eurocentric notions of contemporary dance, yet an apparent specificity and great precision, which left people feeling 'oh, this must be traditional dance', or, 'an immediate framing of the work as decorative!' I think. In the presentation of the work, the question was, "How do we bring the audience to a point of concentration? And how do we frame the work in a way that it makes sense, or there's a certain accessibility?"

This film, I think, from Théâtre de la Ville is the moment when the audience is entering the performance, so there's a lot of talking amongst the audience. As the audience is walking in, the dancers are already standing there, hoping that this moment of noise when the audience is coming and doing all these social things would dissipate. But we were mistaken because the audience just keeps talking anyway! That didn't work out. There's a moment when the sound begins. People are still walking in, but I actually propose not the performance, but somehow the grammar that I develop towards the building of the performance.

It was partly my own curiosity through this strategy of 'framing' my own show in what could easily be mistaken for exoticism, to play with the misconceptions and clichéd ideas that surrounded any unfamiliar work. And still... a certain reluctance to engage 'the other' with intellectual rigour and curiosity. Much easier to just dismiss work that isn't served up on a platter, easy to consume.

Starting with my first solo in 1993 up until the next work that I made (Pushed, 2006) which I'll also show a short clip from, I refer to this phase of making somehow as for me a narrative phase, though it doesn't seem this way. There was always for me a concern about the necessary connection of form and content. I was convinced that it was this logic of evolving movement material that would answer the questions of what the work needed to say or do, that would save dance from actually what it is—ultimately meaningless! As a choreographer I was never looking at developing one way of making work, to find one form that I would just adapt to different situations. But for me every work began really with thinking, "What do I really want to say with this work? And then how do I evolve a form that can appropriately communicate what I want to say?" That was my process until 2006 with the work Pushed, and the processes were always long often taking between one or two years of continuous work. And then, something shifted. We'll just watch this for a while.

Out of the line of five of us, there are three of us, myself, Krishna Devanandan, also was a colleague of mine in Chandralekha's work, Preethi Athreya who was also a Bharatanatyam dancer, now a choreographer, and two dancers who didn't come from a classical training. The ecosystem of the group started to change in this time because, as it was already at the end of Chandra's time, we understood more and more clearly that Bharatanatyam dancers in Madras were not so intrigued by this proposition. Dancers started to come from, either completely untrained dancers, or people who had done some athletics or a little bit of ballet, something like this. But there was always an intense focus on pedagogy. Paperdoll took three years to be made. After this, I got a little bit quicker. A lot of that time was actually in the training as well because I was in those years, more than today, very specific about technique.

Paperdoll with all of the backing of big presenters of the early 2000s, which I think was actually a time when the world—also politically, but then somehow reflecting also in the cultural landscape was much more open. I think curators like Frie Leysen (at the time, Kunsten festival des arts) very insistent on just not so much judging but giving space to the other, is how she called it. People like Gerard Violette (Theatre de la Ville), who always looked to Indian dance for certain amount of his own programmation, and so with a certain ease, I felt that the work had a certain kind of attention at that time.

Through one of the tours of Paperdoll, I met some curators from S.Korea... Until then I had only been sort of circulating in Europe, a little bit in India, and for the first time in 2006 I had an amazing and very generous invitation from the Seoul Performing Arts Festival, who commissioned a work from me in a very odd way. And the commission was, "You can make whatever you want, but your composer has to come to Korea and work with traditional Korean musicians." They were very interested in the way that Maarten Visser and I were working with traditional form and instruments in a completely new way. They wanted Korean musicians and the dance community there to encounter this process. And this was the offer, so it was actually I think a musical commission with a dance performance attached to it. And this piece was Pushed.

But to go back to that transition, because for me this talk is all about these transitions. Paperdoll was a remarkable success, but in a way, for me artistically, it backfired in the sense that the work still somehow was perceived and therefore successful because of exoticism. Which I actually only realised later when I made the next piece, because when I went even further in my own research into the next work, which I'll also show you, Pushed, the comment was, "Oh, this is too abstract, and we want something a little bit more decorative like Paperdoll." There was all the time this kind of conversation around, "How far can an artist from India deviate aesthetically, formally; how intellectual, how dry can that work be? How Indian does it need to be? What is it really to be Indian?" And all of these questions constantly, and still, I think, somehow floating and revolving, and creating a certain kind of problematic and highly limiting space.

With Pushed, because of the nature of the choreographic offer, it became somewhere a piece where I allowed myself to fully just follow a certain kind of research on space, that I had not done in Paperdoll, which was a more contained piece. While in Paperdoll, the five dancers never left the stage, for me it was very important to do something very contrary in Pushed. This is a work where the whole work, as you'll see, a little bit, is about the coming in and out of dancers. But also, somewhere I can see, looking back at it, that this was, I think, the moment I started to really look at dance as image. Later on we'll revisit that idea. And in this piece also I was lucky to have the chance to work with the wonderful lighting designer from Delhi, Zuleikha Allana, who was very uncompromising and very meticulous. Somehow her work became a very important part of the performance too.

Those ideas of "How do bodies hold time and space?" became clearer for me. In comparison to Paperdoll, the reception to this work was very difficult, and I was predominantly told that the work was too abstract for Europe. The work had surprisingly remarkable success in India. The piece was actually exploring emotion, not in terms of it's expression but rather a looking for the bodily image of emotional ideas. This starting point was derived from conceptual ideas that lay in the theories of traditional Korean sound, but also in our own Navarasa theory. It was for me also as a physical exploration, somewhere important to go further into this movement away from power and stability, but to really always look for this edge between balance and imbalance, or dependence. All of these sorts of ideas, which for me were also coming into the way that I framed the ethics around my work, and in my working with dancers as well.

As I said earlier, that was for me the end of a certain era of working, where I still had a feeling that dance could change something in the world. At this point I became quite disillusioned with the whole project of 'convincing the world', of being the poster girl for contemporary Indian dance, of trying to fulfil or satisfy the curatorial demands. I wrote in a text before I made the next piece that I don't think dance can solve any of the political problems of the world, and so I want to simply make a beautiful thing. I began two wonderful collaborations, with the light designer Jan Maertens. I called them 'Beautiful things', and I let go of the need to be 'meaningful', and rather allowed a rather self-indulgent exploration of structures—bodies in space and time, rhythms, yet all the while more and more insistently centralising the body as the principle tool for research. And just to say, because I often ignore him, but the music/sound for all my work since Fragility is Maarten Visser, who has over the last twenty years been very closely working alongside my own processes creating a very unique almost translation of the unspoken into sound.