ASIA HUNDREDS is a series of interviews and conference presentations by professionals with whom the Japan Foundation Asia Center works through its many cultural projects.

By sharing the words of key figures in the arts and cultures in both English and Japanese and archiving the "present" moments of Asia, we hope to further generate cultural exchange within and among the regions.

Before Imprisonment

Good afternoon, everyone. First of all, I would like to thank the Japan Foundation and Professor Kei Nemoto for giving me this chance to talk. I think freedom is not just a given right, but a conscious choice. This belief was proven to me especially when I was in prison in the mid-1990s. Please let me share with you some stories of mine.

I took part in the 1988 democracy movement and had been working for the Information section of the National League for Democracy (NLD). I was lucky enough to be safe in July 1989 while our leader Aung San Suu Kyi was put under house arrest after the military regime raided her compound. However, I couldn't stop my political activities against the National Convention which moved toward drafting the new constitution instead of transferring the rule to the NLD, the winning party of the 1990 general election. Then, on October 10, 1993, I was sentenced to twenty years in prison―seven years under [violation of] the Emergency Act 5 (J), three years under the Unlawful Associations Act 17 (1), and five years each under the Unlawful Publications Acts 17 and 20.

Actually, I was a bit happy to be in prison since I wanted to write my own prison memoir, and, for this, I thought I needed to give up freedom. But after sometime, I learned that prison cannot make me give up my will for freedom. Of course, I was locked up in a small cell, alone in solitary confinement: I was not allowed to read or write, and was not able to contact any friends, relatives, or colleagues. My world was the 12-feet by 8-feet prison cell. I was not allowed to do this or that. The many rules, regulations, and instructions I had in prison made me think a lot [about freedom]. I kept asking myself, "As a prisoner, can I not do anything anymore?" But my answer was always, "No."

I still believe that no one can hurt me without my consent. I reminded myself to keep my authority and told myself that prison should not be the challenge for me. The real challenge would be the way I face prison itself. I still believe that faith might not be changed, but the way we face good or bad faith can be chosen by our own authority. My choice of [either] fighting against or fleeing from a given situation should be free. This freedom is my own right or property. Then why should I give up this freedom? Until and unless I give up my freedom to choose the way I face all life challenges, I will not failed. That is why prison [itself] didn't bother me. Instead, I challenged myself to freely choose the way I live my life in prison.

Here, I will read some passages from my prison memoir, Prisoner of Conscience: My Steps through Insein. It was written only ten years after I was released from prison and got published first time in my own language in late 2012. The English translation of this book was published in 2016. I was terribly ill in 1995 and the following is my experience as an illegal prison. Here it goes.

Days in the Insein Prison

On 7 June, my condition got so bad that my fever was high, I was either vomiting or belching, and there was also spotting even though it was not time for my period yet. With the cleaners' help, I placed the drinking-water pot, the washing-up basin, and the covered waste basin around my bed; it looked like a Burmese drum circle. Then, some guards arrived at my cell, started to pack my belongings, and said they were going to send me to Insein General Hospital.

This was how I was able to go outside of prison after nearly a year in the infamous and notorious Insein prison. Let's move on.

We reached Insein General Hospital in the dark. There would not be any chance for me to know a taste of freedom as I was still in the white prison garb upon arriving at a familiar environment where I used to be in a white duty coat with a stethoscope draped around my neck. To strangers who saw me in prison garb and escorted by guards, I was only an ill criminal coming for treatment at a public hospital. I walked in feeling embarrassed to be seen like this but also wondering why I should care, while bearing my pain with every breath.

It was already dark that night, so I was given some intravenous injection by some junior doctors, but no senior doctor showed up. Next morning, at about half past eight, the gynecologist arrived to examine me. However, before she began, she received a call from the medical superintendent of the hospital demanding my immediate discharge and for me to be taken back to prison.

We could not understand this and were surprised as well as disappointed. Dr. Daw Khin Than explained that she had not even checked me yet, but the superintendent asked her to just do it quickly and have me write and sign "Discharged by Request." The medical superintendent could not resist the demands from the chief warden and the prison doctor.

Then, with strength rising out of adrenaline, I turned to the chief warden and women's doctor-in-charge and said, "It's your wish to take me back to prison without getting any treatment. Therefore, whatever happens to me will have nothing to do with this hospital and doctors, and nothing to do with me, either: it's all on you, completely. I warn you, this is your responsibility. Remember that!" I climbed up the steps of truck with all my bags.

Back in the prison, a nurse came to tell me that I had to keep all my medicines in the prison clinic. I could not accept this; my parents bought these medicines for me and I often shared them with others in my block.

Then the women's doctor-in-charge herself came and told me sternly that since I had said it was their responsibility if anything happened to me, she had the responsibility to be in charge of my medicine. They forcibly tried to pry away my medicine basket from my grip, and I used all my strength to hold on to it.

I declared hunger strike, warning her, "

... let's see how much a person like me, who's had a fever for straight six-month and weighs eighty pounds. So saying I stalked out of my cell, my steps swift with anger and my body shaking like a leaf......Just as I expected, within fifteen minutes, I heard the sound of "Line up! Line up!" I sat up on the bench. The iron door of our block swung open and a few uniformed men walked determinedly toward me. Some wore stern looks as if stalking prey and some wore friendly looks as if to manipulate me.

They asked me what my demands are.

I bluntly answered, "One, I can't allow my medicines to be taken away. Two, I won't take any treatment from the women's doctor-in-charge and would like my case to be handled by another doctor."

I also asked them why they wanted take my medicines away.

"That's because you might use these medicines to kill yourself. You could do it, too, because you understand everything about medication," said Deputy Chief Warden U Ohn Lwin in a gentle tone....... "If I wanted to die, even if you left me, pardon me, naked in my cell, I could still keep hitting my head against the wall to kill myself. My problem here is to stay alive and well, not to kill myself. I don't want to die. Having had no effective treatment for my illness, I am asking for these two things in order to live, Uncle." My voice became calmer......"Actually, what you are putting me through will surely kill me, Uncle. That's why I said that the prison must take responsibility for any consequences of me not getting treatment."

Ma Thida, you're the one who's free.

Then the medical in-charge tried to intervene and console me but it was not reasonable, so I strongly responded via a human rights perspective to all of them. Finally they gave up and agreed all of my demands. So my hunger strike lasted less than an hour. But just before we finished our very intense conversation, the Deputy Chief Warden told me, "Let me say, Ma Thida, you're the one who's free."

Ma Thida, you're the one who's free. Ma Thida, you're the one who's free. Those words echoed in my ears. Although I knew what he meant I asked anyway, "What do you mean? Are you saying I―locked up behind these doors in a twelve-by-twelve-foot cell for twenty-three hours, fifteen minutes a day―am the one who's free?" "You can say what you think, but we are civil servants. Please understand us." His voice faded as he spoke. The others were so quiet one could have heard a pin drop.

After this, my fellow inmates waited to hear my story of the very short period of freedom at the outside hospital. But for me, I could not wait to share my other kind of "freedom" with them: Ma Thida, you're the one who's free.

Remembering the deputy chief warden's words, I realized that I had never let go of my freedom of expression in jail.

In this case, I believe that I chose not to lose my freedom. The Warden and guards are free in term of physical and legal conditions, but they are not free in term of idea or practice. But that was me as a prisoner: I lost my physical and legal freedom, but I had my free will to express my opinions and thoughts. And I could also practice my right for freedom to choose to be the one who is free despite being in prison. Therefore, I dare to say that freedom is not just a given right but a conscious choice.

Four Rotten Mangoes

With free will, we can also be creative in responding to things that just happen to us outside our will. Let me tell you another story about my prison days.

I was diagnosed with a serious form of endometriosis which infiltrated into the deepest part between the rectum and vagina in late 1998. This was the consequence of having no treatment for the endometriotic cyst since 1995. As I got acute liver shutdown for taking both anti-Tuberculous therapy and hormonal therapy for this cyst, I needed to stop taking hormonal therapy.

So my condition was poor and my gynecologist from the central women hospital allowed me to get fresh fruit and food for the intense constipation that resulted from the disease infiltration. In prison, we're provided with very poor quality food and our family members are allowed once in two weeks to give us only processed and dry food. So having fresh fruit and food is a privilege for others, but for me it was a necessity. Here is the story.

One Tuesday in early December I received her parcel as usual, but four mangoes on the list were missing. I handed the parcel back to the trustee prisoner who brought it to me and asked her to report that I would accept the parcel only if it came back with every item on the list. Within a few minutes, she came back and said to me, "Those mangoes were not confiscated, they were just not allowed."

I told her to go back and ask why as I had permission from the doctor to eat any fruit, including mangoes...... After a while she returned with a young guard who said that there was an outbreak of diarrhea in the men's side and since mangoes soften the stool, they had been banned.

I replied, "Exactly, I need to eat mangoes because I am very constipated―that is why I need them back. If I can't have them I won't accept the rest of the stuff." The guard went away again, sniffing in disapproval.

She returned soon and said, "......all mangoes are banned."...... I told her, "No, I cannot accept this. Go back and ask them who made that decision, I want to know so I can ask that person directly." The young guard went away again...... She soon returned and said, "......This order came from the chief warden and they said the decision wouldn't change no matter whom you asked."...... I sympathized with these two women but thought I needed to teach a lesson to the chief warden and his staff. "All right, take those mangoes and this list and give all of it back to my mother and get her signed note that she has received the four mangoes. Only then will I accept the other stuff in the parcel." Sighing heavily, she left.

When two young women came back, the guard, said,

"Oh, Sister, just let me die! Your mother's gone already, she left once the parcels were taken in. What do I do now, huh? Do you want me to follow your mother to your house and ask for her signature that she has received these mangoes? Is that what you want?" She said this tauntingly, and I taunted her right back, "I might, if I were like in the old days. I would've set the whole sky ablaze with my temper. But now you can do this: go tell that officer who confiscated my mangoes to keep them until my next prison visit and she can return them, good or bad, to my parents right in front of my eyes. If she can promise me that, I will accept the other stuff." They again hurried back to the office.

The truth was that I could not accept the idea of the staff taking even one hardboiled egg from families who could only afford to send in ten for their loved ones in prison. They often took whatever they liked with the excuse that it was not permitted. I knew that the value of four mangoes was nothing, but I wanted the authorities and guards to know that they could not treat everything as theirs just because the stuff belonged to prisoners. It did not matter whether I could eat the mangoes or not. Soon after, the authorities sent word that they promised to return them to my mother and asked me to take the rest of the things.

I told the guard, "Okay, take note and tell the other guards here too that you can't just say something is not allowed and take away anything from what the families bring. The real owners are never the staff of the prison, understand?" She did not say anything but nodded.

My parents could not stop laughing when they were handed four rotten mangoes on their next visit.

I gained an even higher rank in the troublemaker category after that episode. I could not help it. If we allowed this type of corruption because it was a trivial matter it would keep on happening and we would be accessories to the corrupt system. Even though I was causing trouble like this it had no impact on my morality, integrity, and wisdom.

Excerpts from Ma Thida, Prisoner of Conscience: My Steps through Insein (Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 2016) 109–114, 116, 117, 200–203. Punctuation, grammar, spelling as in original.

With this story, I dare say that even a prisoner or a trivial act could correct the corrupt system. However, I know this wouldn't happen in the long run as people usually contribute it for so many reasons.

There are all together four causes for corruption – Greed, Anger, Fear, and Ignorance. Among these, the most dangerous one is Ignorance. Why? The lack of knowledge, illiteracy, and unawareness are big obstacles for anyone to be strong and independent. If someone is weak and dependent, that person will just rely on either other people's suggestions or one's own emotions. Then they would be subject to greed and anger, forming corruption according to their emotions. Or they would commit fear which will also form corruption according to other people's orders, suggestions, or demands. Therefore ignorance, lack of knowledge, illiteracy, and unawareness are the most dangerous forms and causes of corruption.

In my stories, the knowledge I gained from reading books has helped me to be creative in my response to any situation that I found myself in. Throughout my prison days, the wardens were surprised to face totally unpredictable responses from me: as they had mostly seen prisoners who simply responded to them in very stereotypical ways, their old practices left them unprotected dealing with a prisoner like me. And because of books, I know more about how to practice Vipassana Meditation effectively and systematically.

Vipassana Meditation in the Prison Cell

Vipassana Meditation practice is indeed to liberate ourselves from endless circles of life or samsara [karmic cycle or reincarnation]. I practiced Vipassana Meditation up to twenty hours per day in early 1995 which helped me fully understand my inner self in order to detach myself toward a total liberation from samsara. Learning of myself via Vipassana mediation has indeed made me learn that there are only three basic truths―impermanence, suffering, and no self.

Everything is not permanent so there is only suffering, and these two concepts allows me to be indifferent to both the good and bad. Both are impermanent and cause suffering. So why should I feel overwhelmingly happy for having the "good" or inconsolable sorrow for getting the "bad"? If someone is indifferent to anything, this is liberation. This has helped me a lot in my response to any situation inside prison.

Finally, I would like to say that knowledge and insight gained via books and practicing meditation has helped me to overcome not only physical illness but also psychological trauma in prison. I believe freedom is from within, not from outside.

I wish that you will all choose your own freedom from inside yourself via knowledge and mindfulness, in order to face and respond to the endless challenges in this life.

Thank you.

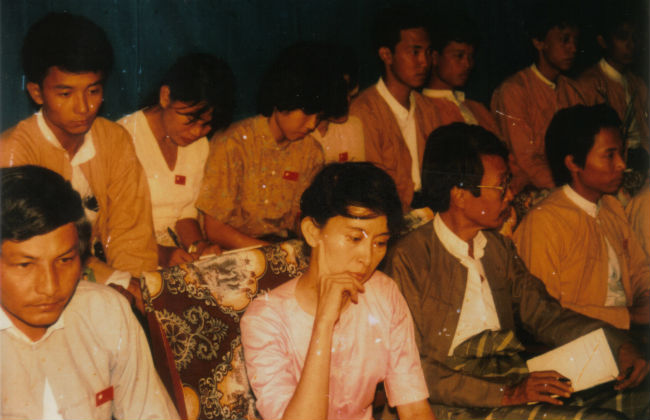

Photo: Courtesy of Ma Thida

Photo (Symposium): Eisuke Asaoka