ASIA HUNDREDS is a series of interviews and conference presentations by professionals with whom the Japan Foundation Asia Center works through its many cultural projects.

By sharing the words of key figures in the arts and cultures in both English and Japanese and archiving the "present" moments of Asia, we hope to further generate cultural exchange within and among the regions.

Wrongly Accused of a Crime

Sayuri Kida (hereafter, Kida): It's now been about a week since the opening of the SUNSHOWER: Contemporary Art from Southeast Asia 1980s to Now exhibition in which your artworks were showed. Have you been able to relax?

Htein Lin: Yes. After it opened, I travelled all over Japan, and I've had a rewarding time.

Kida: I'm sure you've already answered some of these things in previous interviews, but I'd like to proceed by first starting with your work that is displayed in the SUNSHOWER exhibition. I understand that the 00235 series and other works exhibited in this show were made under the harsh conditions of being a prisoner. Not many people experience imprisonment, so I think the first point of interest that comes to our minds is: under what kind of conditions and with what mindset did you create these works?

Htein Lin: At the time, I was putting quite a lot of energy into contemporary art activities, but suddenly in 1998 I was arrested as a political prisoner. Life in prison was very harsh and something I had never experienced before. My concrete room was about 9 feet by 9 feet. Basically I was in solitary confinement. But I had not done anything wrong, and I didn't want to stop my art activities.

Kida: At that time, many people who were involved in the democratization movement were suddenly imprisoned without a fair trial, am I right? And you were one of those people. How did you stay motivated?

Htein Lin: If you think about it, it is obviously quite a desperate situation. But the political prisoners around me, who were there before me, were living very active, vibrant lives while in prison. They did not waste their time at all, but rather continued to critique the military regime 24 hours a day. Just as they, as politicians, were fulfilling their political responsibility to society, I also had a duty to fulfill my responsibility as an artist.

So I came to think of the horrible conditions of imprisonment not as a negative, but rather as an opportunity. Couldn't I use my isolated condition to produce art? Couldn't that lead to art that would be different from anyone else's? I changed my state of mind by thinking like that.

Kida: Opportunity is a surprising word to hear.

Htein Lin: That's because I had the potential for original creativity by using medicine, uniforms, soap, and the other supplies they distributed in prison to create art. I also decided that I wanted to record these facts for the thousands of activists in addition to me who had also been jailed as political prisoners. Actually there were no records of political prisoners' experiences in Myanmar at that time. So I decided that recording it as an artist was my responsibility. That's why I started my art activities inside prison.

Kida: I think you said in another interview something along the lines of, "Even in a prison, where cameras are forbidden, by making art you can record the things that are happening there." I see something of a connection between that statement and what you are saying now.

Htein Lin: In prison, there are all kinds of problems happening before our very eyes, such as the violation of human rights for political prisoners and meals not being given to inmates accused of minor offenses. But even if you wanted to record that, if you're found with even a single ballpoint pen, you'll be punished with twenty lashes. Bringing in a camera is even more unthinkable. But as a painter, I can draw pictures.

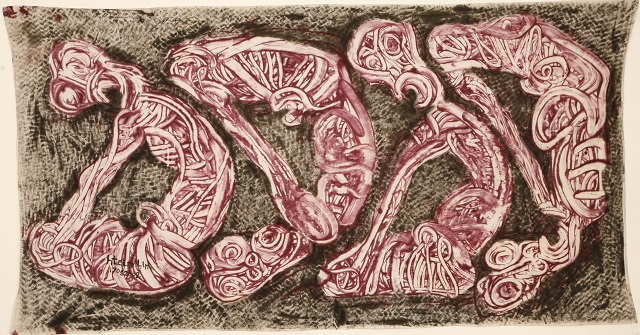

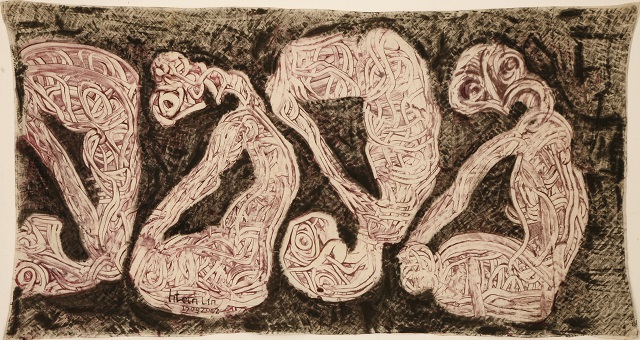

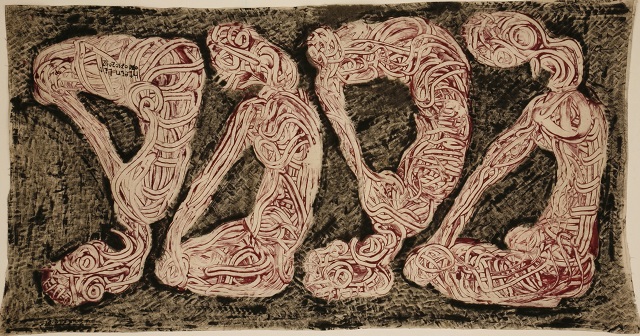

A camera can only convey what actually appears in the picture. But in the case of a drawing, in addition to the drawing itself, you can also include the experiences of the person drawing it. You can show not only the visual elements but also your own outlook on life. As an example, there are several works where I use the way we had to sit while inside the prison as the motif in a work.

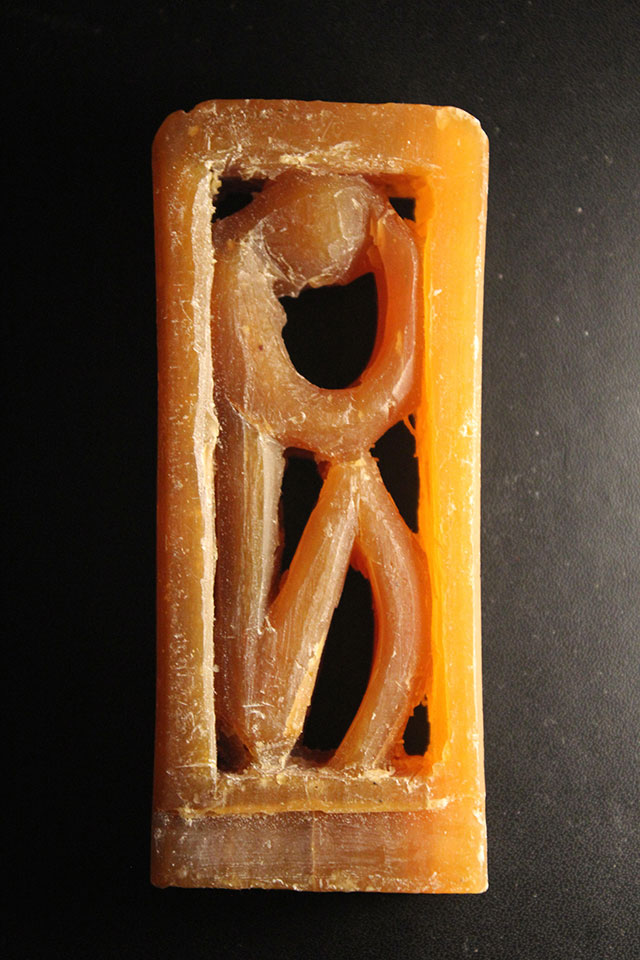

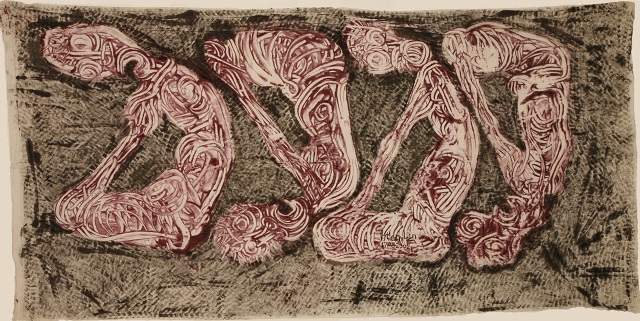

Kida: You're talking about the soap sculpture series called Soap Blocked?

Htein Lin: Yes. Each morning and night, the prison officers came to confirm the number of inmates. During that time, we would have to sit still with our legs crossed, our heads down, with our fists closed and resting on our knees. Until they finish counting, we have to stay sitting like that without moving, so it's very tough. They look at their list and confirm one person at a time, so sometimes it can take around one to two hours. Prison is not a place for meditation, so in a way it could be interpreted as abuse. And if you utter even a word during that time, you will be hit.

If you depict this scene of the inmates huddled in cells, which I called ponsan-tain [Assume the Position] in Burmese, you can only fit a certain number of people in a camera frame, but in a drawing I can make use of the blank spaces too. In Ponsan Tain (2005), I turned the images of inmates sitting upside down and drew them in the blank spaces. In this way, you not only see them sitting, but also can imagine the way their muscles have stiffened up inside the clothes they were made to wear. The reason I drew them upside down is because it shows that their lives have taken a bad turn. That's because most political prisoners are treated as inmates even though they have not committed any crime.

"Drawing" inside a Prison

Kida: In prison, I assume you are not able to obtain paintbrushes or other tools, so I guess you drew using other means such as your own fingers, plastic shards, and syringes. And yet, in conditions where you would be punished for even having a single ballpoint pen, as you mentioned earlier, how were you able to obtain the materials for your drawings?

Htein Lin: Actually in prison, I could not have drawn or produced those works on my own. With the cooperation of the guards, I first had to acquire cloth for example longyis [wrap-around skirts]. It was also necessary to find a place to hide them and store all the materials. After completing one drawing, there came the task of smuggling it outside of the prison. In order to escape scrutiny, there were times when I even put paintings into urinals to smuggle them out. It was also necessary to always stay on top of the schedule inside the prison.

For example. I gathered information on things like which building the prison officers and guards who were usually nice to me were monitoring. Getting the cooperation of other inmates that I lived with was also very important. They didn't just serve as subjects of my art practice, but they also shared their longyis and supplies with me. They shared their belongings with me despite the possibility of getting punished if they were found out.

Kida: Even though you were in that sort of restricted situation, in another interview you said that, in a sense, you were freer in prison than you are in the outside world. Could you elaborate on what you meant by that?

Htein Lin: First, I didn't have to be in fear of things like being monitored or censored by the intelligence agency; second, I never once had to think about putting my artwork on the market and having to make a profit out of them; and third, I was able to make works without concerning myself about the opinions of an audience or critics. These three points, I think, form the backdrop for the works you are looking at now.

The circumstances were extremely restrictive, but in terms of my feelings, I was able to create my own artwork in a really carefree way. At that time, there were informants around the city. So there was a sense of fear that high-level officials or military would be aware of everything that we were up to. But in the case of us political prisoners, we already had a strong belief in our cause, so we were able to come out and express our frustrations about the military regime, for example, without hesitation.

There was no need whatsoever for us to treat high-level officials in the military regime like gods. We were able to voice our opinions freely; even about Senior General Than Shwe, who was the dictator. If we didn't like him, we simply said so. Inside a prison, usually you would fear the warden, the prison officers, and the guards. But taking that attitude actually kept them from approaching us. As a result, we never developed fear toward them.

From my perspective as an artist, in the outside world, if you have an exhibition of your paintings, you would be asked about the meaning of every single work by someone from the military intelligence who would nitpick every minute detail about the work. Even the color of paint you used: if they thought there was a lot of red on the canvas, for instance, they'd ask why. Essentially you would be creating artworks while in constant fear. I promised the people in prison who cooperated in getting me paint, cloth, and other materials that I would not show them until I left the prison. So, again, I was able to produce works freely without the concerns of having to make art for exhibitions.

Kida: Others such as Nelson Mandela and Victor Frankl have also written about freedom inside the prison. Your words, too, makes me rethink about the concept of freedom, and what it means to "be free."

Htein Lin: At first I thought freedom was something that the military regime held. But when I first realized that I had so much freedom even while being confined to a 9 by 9 room, I was very surprised. When I became aware that I had obtained that freedom, I thought this was indeed an opportunity, and I felt like I needed to be continually active.