Collaboration as a Methodology

Takiguchi: Let me ask about the language. Ten Thousand Tigers was a multilingual production in Malay, Chinese and Japanese. No English was spoken, which means the text you originally wrote in English was not spoken on stage. In contrast, we heard only English in One or Several Tigers. The multilingual experience in Ten Thousand Tigers was quite different from the monolingual experience in One or Several Tigers for me as an audience member. How do you see the plurality of the language, or voices, in a production?

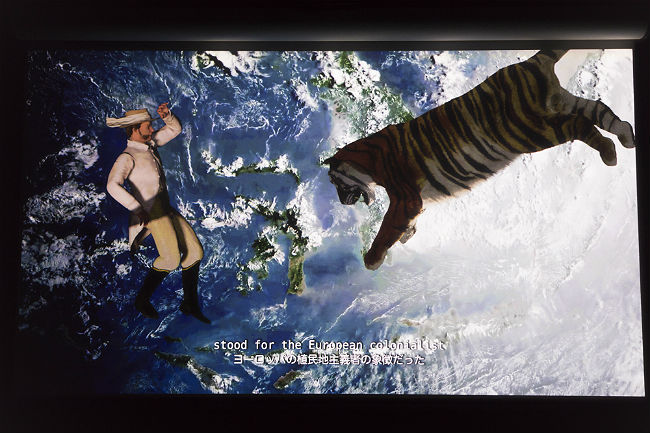

Ho: It is a good question. I would say that we hear a multiplicity of voices in Ten Thousand Tigers, but the actual concrete experience of the work is still reduced to a single language, which is English. This is because all of these languages are translated into subtitles. We cannot forget that the subtitles are just as much a part of the piece. Sometimes we think that the subtitles are an external part of the work, but I do not agree with that. Thus, the set of Ten Thousand Tigers was designed specially by integrating the subtitles projection into the "shelf".

The subtitles – or surtitles as they are called in the performing arts context – appeared in three areas of the shelf. So where the subtitles appear, the audience's gaze is drawn into a particular part of the shelf. The subtitles are very much a part of the performative experience. I sometimes think of Ten Thousand Tigers as a comic strip or a graphic novel. It was a theatrical form in which the audience members were invited to read, while they simultaneously looked at the images and objects I had gathered. Reading the text, looking at images and thinking about their relationship – this is quite similar to reading a graphic novel. Thus the three spoken languages become materials for me, which are both sonic and historical. The languages express intensities in modes specific to the historical specificities of their speakers.

Going on to One or Several Tigers, I worked only with one performer, the musician and singer Vindicatrix, who speaks a single language. However, he spoke as both the Malayan tiger and the English – actually Irish – surveyor working for the British. Thus, he is a single voice that not only splits into these two opposites but also performs the chorus, which are lines that belong neither to the tiger nor to surveyor.

The mode of utterance in One or Several Tigers is quite clearly musical. But the lines in Ten Thousand Tigers were delivered in a mode somewhere between singing and recitation and chants. I must say that I always had great discomfort with speech on stage, especially with Singaporeans speaking English on stage. This is probably due to my own personal difficulty. I grew up speaking Mandarin but was, like all other Singaporeans, educated in English. Now I am speaking in English with you, but I have the perpetual sense that there is a gap between my brain and my tongue. I have always felt like I've had no mother tongue, and that I do not have a linguistic 'home'. So I have the fantasy that the only way for me to circumvent this gap is through the musicalization of speech.

Photo by Hideto Maezawa

Takiguchi: I remember that during the creation of Ten Thousand Tigers, there was a session where three translators – of Chinese, Malay and Japanese, which was myself – gathered. We of course translated the part assigned to each of us individually, and the session was meant for adjusting the tone and nuances used in each translation. You gave us very detailed comments on the choice of the language in a particular scene. That kind of orchestration should be pretty important for the multilingual theater.

Ho: I was just pretending to be orchestrating the three of you, because I had of course no idea what you were translating. I had total faith in you! But I try to provide as much ideas and associations as possible when I work with collaborators. But at the very last instance, it is an act of faith.

When I worked with the musician for One or Several Tigers, I wrote the script and at every line of the script, I provided a precise timing for how long each line could be. I also gave musical references as to what it should sound like. At the end of the day, the musician created something that was immediately powerful and beautiful to me, but yet, at least on the first few listenings, didn't sound anything like the references that I had in mind. But this is the beauty of collaboration, isn't it?

I always like to start by creating the most detailed map before starting to work with my collaborators. But I am prepared that this detailed map would be transformed into something else by my collaborators. I like to give them the freedom to imagine and think as much as possible. I consider my detailed map as a safety net or a bedrock – my collaborators are free to push the work but can come back to that when they are lost in the creative process.

Takiguchi: How do you describe your role in that kind of collaborative process? A director? A conductor? Or something else?

Photo by Hideto Maezawa

Ho: I really don't know either because I am neither from a filmmaking nor theater background. They are just strategies that I have developed for working together with people across different fields. But I sometimes feel close to the processes of certain composers from a very particular era. I don't understand musical theory, but I am a big fan of music, so I try to read up about composers such as Iannis Xenakis.

From what I read, Xenakis composes in a way that is at once extremely detailed, but yet this complexity and density is that which paradoxically demands his musicians' interpretations. I think he referred to this as a stochastic process, which is different from John Cage's chance operation. It is a controlled flow of different layers. You cannot predict how everything would turn out, but you still somehow manage the flow of the whole. This might be the closest description of how I conceive of my collaborative process.

Takiguchi: It seems that many artists are now working beyond the traditional segmentation of genres. In last year's TPAM, for example, Apichatpong Weerasethakul's Fever Room was shown. This year's TPAM is showcasing even more interdisciplinary works. How do you see the interdisciplinary works by other artists?

Ho: I seldom think about whether I am interdisciplinary or whether a work is interdisciplinary. These considerations do not come in when I am conceiving my work. But I do think that interdisciplinarity exists within every art form even in earlier periods of history. It is just that they were not commented upon as such. For example, the 18th Century French painter Antoine Watteau painted scenes that seem like they were depictions of myths. We don't realize it when we see them today with our contemporary eyes, but they were sometimes actually depictions of plays that the aristocrats put on for their own pleasure.

I think that our notion of interdisciplinary works today is a reaction to the modernist period when the holy grail of art was to find the essence of a discipline. In painting, for example, we have the myth that the great modernist painting is about finding what the essence of painting is, which brought increasing abstraction and flatness to paintings because painting on a canvas is supposed to be flat – thus they got rid of perspective. So perhaps the concept of the interdisciplinary is a kind of reaction to that, a way for us to say farewell to the modernist era.

At the same time, however, I do think that it is a positive thing that we are able to circulate our works beyond the confines of disciplines or genres. What I, as an artist, try to take responsibility for at least is to understand the specific history of each genre. I do not mean to understand the essential truth of the discipline. What I mean is that I try to keep myself informed about the historical fact of how various disciplines I work with have been developed.

Takiguchi: I have one last question, which is about Japan. Japan does not simply sit in the east-west dichotomy, especially from a Singaporean perspective. It is a nation of the east but at the same time, a country that once colonized Singapore. How do you see the position of Japan?

Ho: That is a very interesting question. Actually, it is a topic that I began to take a big interest in last year, and I will probably deal with that in one of my future projects. I recently came across a very interesting book titled The Philosophy of Japanese Wartime Resistance by David Williams (Routledge, 2014), which contains a complete transcript of a series of three conferences held by the Kyoto School of philosophers from 1942 to 1943, an intensely dramatic period in the war. Looking at the title of the book, I had at first imagined that these philosophers were against the war. What then struck me when I began reading it, is how actually all of them were for the war, which they perceived as Japan's historical duty to prevent the eventual domination of American liberalism – essentially it is what happened after the war in a different way. What they resisted was the particular way the war was fought. In many ways they were flawed utopians, who both glimpsed into the future and yet were blind to the conditions of their present. Reading this book, I started to see a whole different perspective and narratives of what led to this war.

It is something very different from how we understand the war in Singapore. When we Singaporeans think about that period of history, we perceive the Japanese involvement in a one-dimensional and entirely negative way. What I got from the book is not justification for war, but it allowed me to understand a little bit the complexity of different forces and reasons going into it. I am quite interested in trying to unpack this period of history and seeing the entire network of ideas.

The issue of war and Japanese occupation is still hard to speak about in Singapore and of course in Japan as well, I am sure. I think – I hope – it is time we are able to – we might not have all the answers right now, but at least to start this conversation and to start thinking in a way without reducing the historical complexities.

[On February 21, 2018, at the KAAT (Kanagawa Arts Theatre)]

Interviewer: Ken Takiguchi

Ken Takiguchi is a dramaturg and translator. Takiguchi was based in Malaysia and Singapore from 1999 to 2016 and has participated in numerous intercultural theatrical productions. Holding a PhD from the National University of Singapore, he is a founding member of Asian Dramaturgs' Network. He is currently working at Setagaya Public Theatre in Tokyo and teaching part-time at Tokyo University of the Arts.

Interview photo: Naoaki Yamamoto