Lily Yulianti Farid (hereinafter Lily): What inspired your writing for YOMU? How did these ideas develop?

Intan Paramaditha (hereinafter Intan): The pandemic sparked a lot of heavy conversations and complaints, but as a writer, it's weird not to have any written reflection about our current situation. But, I suppose it takes time to digest all that's happened.

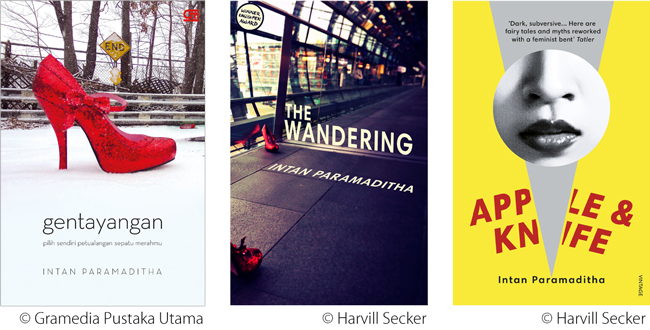

My experience this year was vastly different from the last. Last year, when COVID-19 was declared as a global pandemic, I was in London to promote my book Gentayangan (The Wandering). We had planned to tour for two months, and it was all set. I took a leave of absence from the university I taught at, my publicist organized everything, then I got there and after one stop it was all over.

I got sick in London, but I don't know if it was COVID-19. After I got better I decided to return to Australia. It was a traumatic experience. This year, by contrast, I didn't care anymore and my writing flowed. Maybe I accepted that until the end of 2021 I wouldn't be able to get out of Australia.

I considered my privileges during this pandemic. I'm an introvert who genuinely enjoys solitude and working on my writing for hours. I have a house that's comfortable and allows this process to happen. A lot of people aren't so lucky. My students live in cramped dorms, shared with other students, and there's no space to write, let alone access a library.

I felt guilty for being able to do a lot of things and write productively.

Azhari Aiyub (hereinafter Azhari): I lived in Aceh, where coffeehouses are everywhere and serve as sanctuaries. I thought of writing about this at first, but then I decided to write something more reflective. For the past 1.5 years, I found a lot of things, especially when I "escaped" my house in Banda Aceh and went to more remote places, where people had stronger things to say about the pandemic.

In the past, I had to come up to them and ask them, but these days they seek other people out. They would ask me if this pandemic was real, tried to educate me about the dangers of the vaccine, and so on. At first I pushed back and tried to debate them, but eventually I relented. I just want to listen to them and understand how they receive and pass on this information.

The truth is super interesting. When I was at Sabang, a rickshaw driver waited on me in a coffeehouse for over an hour. He wanted me to ride on his rickshaw, because tourism was gone and nobody had any money. I thought, why not, so I went around town with him for two hours. The entire time, he showed me these YouTube videos about the dangers of the COVID vaccine. I thought these encounters were useless to write about, but then I realized this was happening all around me.

I wanted to convey this by looking at the durian phenomenon. This is a sacred fruit. We plant it everywhere, it's cheap, and everyone can access it easily. But when COVID-19 happened and people got bored, Aceh went durian crazy. People went on day trips to plantations with their families and reopened old plantations. Everything was diverted there.

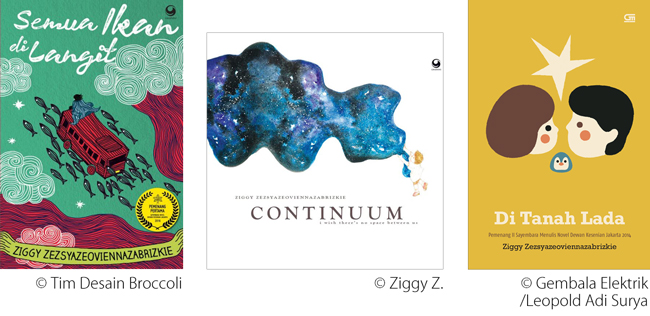

Ziggy Zezsyazeoviennazabrizkie (hereinafter Ziggy): I have no idea what's happening out there because I genuinely haven't left the house since the pandemic. I've always been a homebody. "New Normal" is a strange term, because for me this is normal! But I know this lifestyle isn't for everyone. My Mother got concerned for her mental health because she's used to meeting a lot of people.

It feels new, seeing everyone be forced to accept my version of normal. My small world got big quick like a Peking duck. This desolate world becomes noisy all of a sudden. That's what inspired my writing. My family used to work outside the house, but when they're forced to be at home and I have to see their lives, of course there are things I'm disappointed about.

The conflicts turn internal. My mother's afraid of needles so she refused the vaccine, she asked us if she can drink the vaccine instead. My father won't accept the vaccine until his office forced him to take it to fly to another city. My siblings are workaholics, so I have to take care of their babies. My aunt, a former nurse, died of fatigue after caring for people around her. My grandmother collapsed and died of anxiety. The virus didn't directly do this, but it led to everything.

Lily: Was it harder to write during the pandemic?

Azhari: I thought it would be easier to focus, because I enjoy solitude. But after six months, I suddenly stopped. It feels like I lost something. Usually, after I write, I would go to coffeehouses to meet my friends. My friends are still hanging out there, but I'm too afraid to go! [laughs] This pandemic freaks me out.

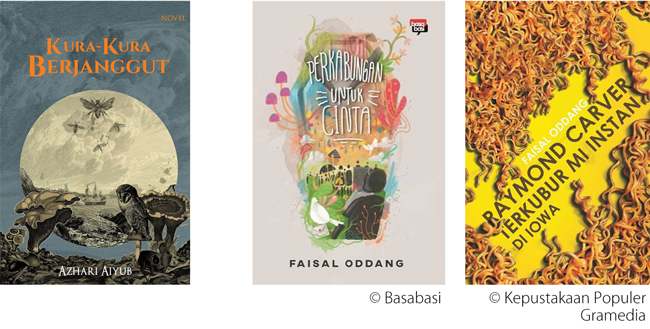

But I think these are the best times during this pandemic. Friends I haven't met in decades suddenly came home and had time for us. They came home and can't go anywhere else. As fear receded, we can meet up and collaborate. I'm doing an adaptation of my novel Kura-Kura Berjanggut (The Bearded Turtle) in a different way. Doing it together moves things along quickly.

Lily: Faisal, your piece for YOMU talks about dreams. Did you know all along you would write about this, or was it spontaneous?

Faisal Oddang (hereinafter Faisal): I couldn't write anything during the pandemic. For everyone else, staying home means having time to think and write. For me, it means having more time for anxiety.

My in-laws' home in Gowa and my home in Maros are close to the mosque, so I hear them announcing people's deaths every day. Everything feels close. I checked in Google Maps, our home's distance to the COVID-19 cemetery is only two kilometers. That's why I hear ambulances all the time.

This caused my anxiety throughout the pandemic. So when YOMU asked me to write, I felt I had to accept it so I can gather all these anxieties and turn them into writing. Concerns about death rattles emanating from the mosque, the sounds of ambulances passing by, and strange dreams.

One time, I started talking in my sleep. I never did that before. My wife told me that while I was asleep, I said, "Don't mess with me, I'm in a swab test competition!" I didn't believe her the next morning. It sounds so farcical! Why would anyone do a PCR competition? From there, I got the idea of a character who can control their dreams.

After I came back to Makassar, my friends asked me to teach creative writing courses for the blind. I learned a lot from them about the pandemic. When social distancing became a thing, they struggled. People used to help them cross the road, now they're afraid to approach each other. They used to identify things through touch, now they're being told that this is dangerous. I asked them if it was okay to incorporate these experiences in my piece, and my short story was born.

Lily: How about you, Agustinus? I heard that during this pandemic, you lost yourself to meditation and stocks!

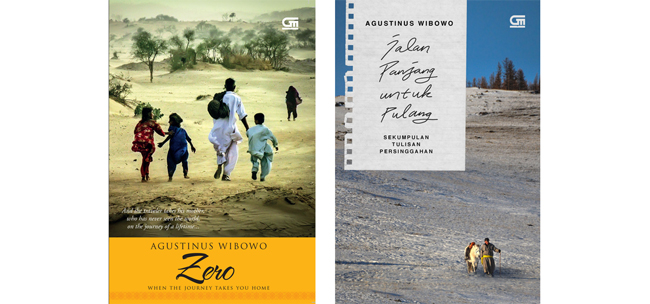

Agustinus Wibowo (hereinafter Agustinus): I had the privilege of being able to live without the internet. I could go ten days without signal and internet and I would be fine. For the first six months, I felt the pandemic was good to internalize and practice my creativity. But then my finances went awry, book tours got cancelled, I can't meet my readers, writing classes got cancelled, and I freaked out.

I experienced lockdown during the SARS epidemic in China in 2003. But Chinese lockdowns last two months, max. Why doesn't our lockdown ever end? [laughs] But if we don't adapt, it's over for us. A friend asked me to teach an online writing class, and I set up a WiFi router for the first time at my home.

From the internet, I learned that these days it's easy to learn something new. As a student, it's easy to gain knowledge from others. I learned psychology from YouTube, and began watching a lot of snake videos. Here's the story: I would have recurring dreams of being bitten by snakes, so I watch snake videos to fight my trauma. Eventually the snakes in my dreams start looking pretty and kissable! [laughs]

Somehow I ended up trading stocks. Stocks and cryptocurrency became a thing in Indonesia, so much so that people started talking of a Corona Generation that became overnight traders. When I ate in canteens and food stalls, people around me were talking about stocks, cryptocurrencies, graphs. I started attending classes and studying, and for a month I dreamt of stocks. YouTube changed my life!

YOMU asked me to write when I was at the lowest point in my writing career. I'm questioning myself because I changed so much. It's difficult to read a book and think critically, but it's easy to analyze the stock market. A friend quoted a passage from one of my books, and I forgot I wrote that. I felt like I had to find myself again.

After talking with a friend, they suggested I write about my changes during the pandemic. And writing this piece helped me. After I wrote down all that happened, I realized our world and humanity were being torn apart. On the other hand, there are positive sides people don't talk about. There's a wealth of new knowledge and information that's easier than ever to exchange.

In between all this, there's a phase where we change and start asking, "Who are we now? How far have we changed?" I experienced this with stocks, and only found balance after I continued to meditate. If we follow the world's changes, time will crush us under. Something within us must stay, and balance must be found.

I'm the same person. I realized there's no happiness in stock trading. I'm happy when I'm sharing my thoughts and ideas with others. My friends started teasing me, telling me I should hold workshops on being author-entrepreneurs. That's not such a bad idea! [laughs]

Lily: This pandemic exposes how writers lack protection and access to emergency funds when they come to the government as writers. What do you think needs to change?

Intan: Saying people should be author-entrepreneurs sounds so capitalist, but when we think about it, we struggle to work when all our support systems collapse because we never think about entrepreneurship. Author-entrepreneurs and independent publishers would form communities that buy and read each other's works. I thought, is that the way forward? Maybe it's more sustainable economically, and we can learn something from that.

Azhari: Maybe because I live in a smaller city, it's easier to fulfill my needs. But of course things change. In a normal situation, I'm more picky about the jobs I take. These days less so.

Lily: Do you think this pandemic is entirely novel, or are there historical parallels that create a collective understanding of this situation?

Agustinus: For me, this pandemic is more than a catastrophe. The Black Death sparked changes that led to the renaissance. Maybe COVID-19 led to increased digitalization. After all this is done, these changes will stay. Zoom meetings and IG Live will keep being part of our lives.

Intan: I'm writing a piece about inequality in a world where some people can move past national borders during the pandemic. For me, this pandemic is new and real. Mothers with jobs now face more burdens because they have to accompany their kids on their online classes at home. It's unusual and it should be highlighted.

Azhari: There's an allegory about lockdown. For me, this situation reminds me of the Regional Military Operation (DOM) days in Aceh, all those years ago. That was a lockdown, too, but it was caused by military conflict. It's similar--people have to stay at home, face uncertainty and anxiety, and everybody feels helpless and angry. If they get out of the house, they could die. Back then you can see death coming at you. This time, you can't.

Maybe this is why people in Aceh hate the idea of lockdowns, barricades, border controls, and so on. The government's attempts at communication broke down. Last month, the regional government in North Aceh wanted to impose lockdowns, but it only lasted four hours. People didn't want their movements limited, with or without COVID-19.

That's a legacy of their experience all those years ago. They need to get out of the house. They've only had freedom of movement for a few years, and now they're fighting to keep it. Barricades and police raids remind us of our painful past. This means our attempts to combat COVID-19 are useless. And now, soldiers are guarding vaccination spots. People become even more doubtful!

The state needs to find another way to show that this pandemic is a real threat. They parade around coffins to scare people, but it's not effective. Cemeteries are everyday life for us. Long lockdowns are worse than death!

Lily: What do you think of translation initiatives like YOMU? What needs to change from our industry after this pandemic?

Intan: In my piece for YOMU, I questioned what continues to move and be heard during this pandemic. If humans can't break borders, something else must be able to do so, right? Writings and ideas, at least.

My critique in The Wandering is how globalizations sharpen to focus on privilege and power: who comes in and out, who turns the wheel and who gets turned. Translations are the same. We're focused on English-language translations, and think Indonesian works translated to English must therefore be translated to other languages.

The English language dominates our translation market. And within this world, there are works that are considered to be more marketable than others. Japanese or South Korean literature translated to English will always get a bigger stage than Southeast Asian writers. I think, initiatives like YOMU's important to break these barriers and create new possibilities.

Ziggy: I heard that foreign books translated to Japanese often lose a certain meaning. Apparently, this was because they sometimes translate the original work into English, then translate that into Japanese. So there are two layers of translation where meaning and context could be lost. It's good to know that our works will be translated directly to Japanese, and our stories can be conveyed better.

Azhari: We can't place this burden entirely on our writers, or on institutions with little capacity to promote "Indonesian literature." It's the state's duty. In a wider scope, Indonesia needs a better strategy to promote our cultural diversity—be it through films, literature, or others.

Indonesian Embassies can't just talk about trade. They need offices dedicated to promoting Indonesian culture, including literature. We can't place this burden on writers and limited NGOs.

K-pop became a global phenomenon because South Korea had a long term plan to promote their culture. We can feel the effects now. Everything's Korean now—film, cuisine, music. That takes time and planning. You can't expect these things to fall out as a gift from the sky.

Agustinus: As a translator for literature from Mandarin to Indonesian, I feel there's a concerted effort by the Chinese government to export their literature to the world. They have large subsidies to translate literature and to pay foreign translators. Sometimes, I would earn more from these translations than I would from my own book royalties, and this is ironic.

We're facing up against the market. The problem is, the western readers that supposedly dominate the global book market have certain expectations when reading about books from other cultures. Popular books about Afghanistan would talk about suffering and war. Nobody wants to read a book about happy Afghanis. Indonesian books are expected to present an exotic view of our country. They won't be interested in books about our daily lives.

This is where the government's support comes in. Some books are well-written, but need support to swim against the market's tide. Some works I translated will never get out of China unless the government supports the writer. We can learn from that.

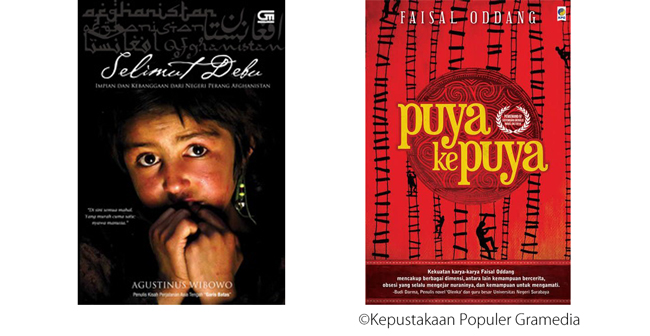

Faisal: Smart publishers are also important. After the London Book Fair, an Italian publisher offered to translate my book Puya ke Puya (From One Heaven to Another) to Italian. I asked, why this book in particular? And they said, the way I spoke about death in that novel is similar to how Italians view death. So, there's a bigger chance that this novel would be accepted by people. From this, we can see how good publishers are able to analyze the context of their own market.