On the Works

Cartographies: Their Sizes and Purposes

Sano: Moving briefly onto your cartographic works which you've been continuing since 2007. I'm curious about their size. If I remember correctly, the largest is about an arm span? How do you determine their sizes?

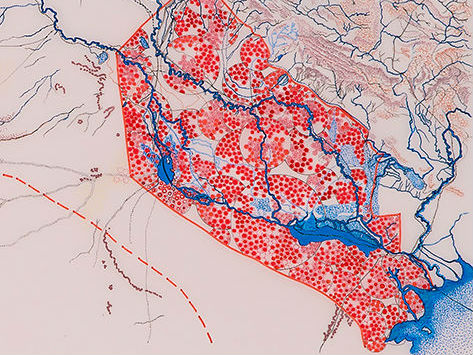

Chung: The largest map drawing to date is 1.8 meters, so yes, it's not tremendously big. But if you consider the meticulous process to cover the entire surface, it is a lot of work.

Sano: I can imagine; with all your microdots, beads, and layering of vellum and paper. Which is the 1.8 meter one?

Chung: The Tangier map.

Sano: How did it become to be that size?

Chung: Well, it involved a few different zones during the Moroccan independence, so I needed a larger surface area. In my monthly tracking of the Syrian refugee crisis, as the numbers quickly increase every week, I couldn't just do one large map. I needed a number of smaller ones to be able to track it. The size, to me, is not so important: It depends on the purpose of the mapping.

Sano: I was always interested in their size especially because you can fold and unfold maps to navigate yourself from both close-up and bird's-eye views. And with The Syria Project, there is that dual perspective: having dozens of small canvases to follow the movement in close-up and also having the larger picture of the crisis.

Chung: Yes, and it'd continue to grow, not just the number of maps but also the sizes of the dots.

Sano: You mentioned you'll be covering the entire globe with your new addition to The Vietnam Exodus project, so I assume it'll be pretty large.

Chung: Several of these maps are about 3 meters or larger. I need to have that size to show their escape routes and migration trajectories throughout the world.

Temporality in Maps, Videos, and Performance: Collapsing Time and Providing an Entry Point

Sano: How do you conceptualize temporality throughout the different mediums of your works? I mean, you also have several video works, one of which is well-side gatherings: rice stories, the rioters, the speakers, and the voyeurs (2011) which was based on your research of the kome sodo [rice riots]*3 in 1918 Japan, which you then made into a theater performance called chronicles of a soundless dream (2012).

With the maps, I understand different temporalities exist from the superimposition of layers or the juxtaposing of several canvases; with videos, duration is already an inherent component of the medium; and performance is a onetime, live occurrence, so to speak. So how do you think temporality plays in with the different mediums in your works?

*3 Kome sodo [rice riots] broke out in 1918 in Toyama Prefecture, Japan, perpetuated by the rapid rise in the prices of rice, a main staple in rural Japan. Newspapers gave national exposure to the riots in Toyama, which triggered similar riots throughout the country.

Chung: Well, one thing that you see throughout my works, in all the different mediums, is the collapse of time. When I layer the vellum or paper, there is already a collapse of the different time periods. With performance, too, the fact that I dig into history, pull out historical accounts of a nation or personal experiences, and have young dancers re-enact that moment, there is a collapse of time. Conceptually, it's about the collapsing of history between, for instance, Japan and Vietnam in well-side gatherings and chronicles of a soundless dream. Japan during the war, and Vietnam after the war: two different time periods, two different historical contexts. And on top of that, you have dancers, living now, who are trying to recapture the spirit of 1918. So while I dig into history, while I excavate lives and geopolitical or social contexts, I am layering time, thus collapsing it.

Sano: But your maps are very aesthetically pleasing, so what is your method of getting the audience to take a step further into the contexts or content of the maps?

Chung: Beauty and aesthetics draw the audience in before they realize they have just got punched in the guts with heavy subject matters. Titles, also, give an entry point into the works.

Sano: But still there is so much history, so much research condensed into your works.

Chung: What I avoid in all my works is to be didactic, to give answers, and to impose my ideas and beliefs on people. You can only give people a glimpse of history through an artwork, not a whole history lesson. I want to encourage questioning, and I want to provide an entry point into the history that the audience might not have known, so that they will take on the responsibility to study the history themselves. Furthermore, I often create a totally immersive experience through multi-sensory installations that include my mapping component, which by no means is the only medium I use. Unfortunately (or not), I'm mostly known for my cartographic practice.

Chung: I am currently trying to put together a lecture performance because, as you say, not everything can be shown in my maps. So a lecture performance on my process in length and exploring the issues that I have learnt through my projects may give the audience another entry point to understand what I go through in order to create such "beautiful" works [smiles].