ASIA HUNDREDS is a series of interviews and conference presentations by professionals with whom the Japan Foundation Asia Center works through its many cultural projects.

By sharing the words of key figures in the arts and cultures in both English and Japanese and archiving the "present" moments of Asia, we hope to further generate cultural exchange within and among the regions.

Today, I will talk about how the politico-historical connections between the Philippines, the United States, and Japan are intertwined with my familial history: how memory and forgetting function in our understanding of the past and how they have continued to shape our perceptions of Japan-Philippine ties. I will not read a long, academic essay. Instead, I wish to present stories organized around photographs that illustrate the complex geopolitical relationships between the three countries from the late nineteenth century to the present.

The Japan of My Parents

Japan is situated in the story of the Philippine nation within a narrative usually dominated by the experience of World War II, the Pacific War, of which my father was a soldier and veteran. I was born in October 1946, one year after Japan's defeat, and three months after the Philippines gained independence from the United States.

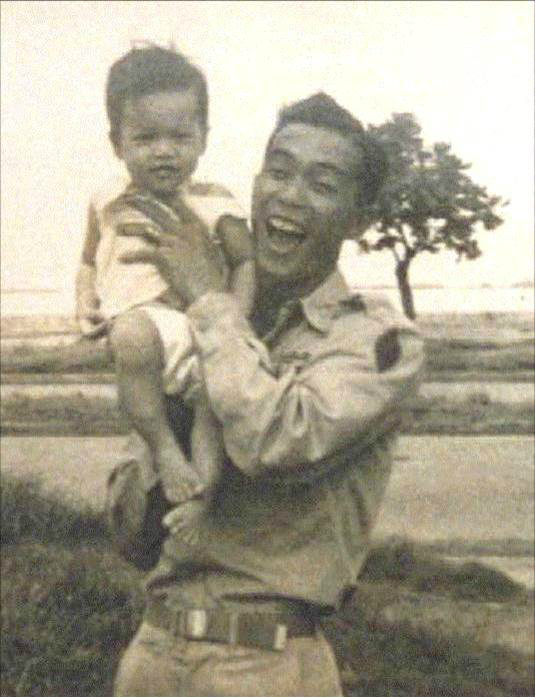

Taken in late December 1946, this photograph shows my father, Rafael, suited in a United States Army Captain uniform, holding me up, laughing. It was during his Christmas leave as commander of a company of American soldiers in Okinawa. Allow me to stress this: a Filipino was "occupying" Japanese land.

Taken in late December 1946, this photograph shows my father, Rafael, suited in a United States Army Captain uniform, holding me up, laughing. It was during his Christmas leave as commander of a company of American soldiers in Okinawa. Allow me to stress this: a Filipino was "occupying" Japanese land.

Born in October 1920, my father was a full product of American colonial rule (1901-1946). He applied to enter the Philippine Military Academy in 1939 and was one of the lucky few who were accepted. As a plebe at the Academy, he performed so well that he was selected, in 1940, as one of the two plebes to be sent for further training at the United States Military Academy in West Point.

Born in October 1920, my father was a full product of American colonial rule (1901-1946). He applied to enter the Philippine Military Academy in 1939 and was one of the lucky few who were accepted. As a plebe at the Academy, he performed so well that he was selected, in 1940, as one of the two plebes to be sent for further training at the United States Military Academy in West Point.

As my father put it, being sent to West Point incurred for him an utang na loob [a debt of gratitude] to the United States. Like all of the brightest young men and women of his generation, to be sent to the United States as a pensionado [government scholar] was the pinnacle of one's dreams. They were also fulfilling the objective of the US occupation to "tutor" the Filipinos to become "modern" and worthy of independence.

My father's training at West Point coincided with a time of war. Japan enters into my father's story not just as the war-time enemy, but as a reminder that he was still an Asian in the eyes of many Americans. A clipping from the The Tulsa Tribune shows just how committed my father was to the US alliance against the Japanese. I quote,

Training as an air force cadet at Spartan, he [Rafael M. Ileto] already has pledged himself to aid in the recovery of his native land from the Japanese. "I'm really going to dish it out to the Japs, just as they did it to my people," he said.*1

*1 "Learning How, Now, Then Look Out! Filipino Trainee Just Itchin' to Smack Japs," The Tulsa Tribune, June 1943.

These are very strong words, indeed. Despite such protestations, however, Cadet Ileto, much to his annoyance, kept being mistaken for a Japanese man himself. This was dramatically illustrated by an incident, described in the West Point magazine In Column, in which he was nearly lynched by a crowd of American farmers.

HOT SPOT-One of our Filipino cadets, obliged to make a forced landing, found himself the immediate center of the excited interest of a crowd of farmers. When the farmers got a look at our cadet, the interest became menacing and rustic weapons such as pitchforks, hoes, and scythes began to appear. Lynching was eminent and only after considerable talking did he convince the mob that he wasn't a Jap.*2

*2 A page from In Column, the West Point magazine.

Throughout my father's long military career, apparently this was the closest he came to losing his life. Ironically, the enemy here was not the Japanese or the Communist Huk*3 rebels, but white American farmers. This incident brings up a ghost of the past: the Philippine-American War (1899-1902), when America's enemy across the Pacific was not yet the Japanese, but the Filipinos.

*3 Abbreviation for Hukbong Bayan Laban sa mga Hapones [The Nation's Army Against the Japanese Soldiers] or Hukbong Laban sa Hapon [Anti-Japanese Army]. A Communist guerilla group consisting of farmers of Central Luzon, formed in 1942 as part of the united resistance against the Japanese occupation of the Philippines.

For my military father, there were two main enemies that he fought during his career: the Japanese army and the Filipino communists groups in Central Luzon. The revolution against Spain [Philippine Revolution, 1896-1898] and the subsequent Philippine-American War were not important to him at all. What figured heavily in his remembrance of the past was the joint Filipino-American struggle against the Japanese in World War II.

This is a photo of the officers of the First Filipino Infantry Regiment, United States Army, taken in San Francisco just before their return to the Philippines with General MacArthur's force. Their story is familiar to any student of the Pacific War: they participated in the "island hopping" campaign (also known as Operation Cartwheel) in the southwestern Pacific before reaching the Philippines. My father, who by then had become a Lieutenant, led a platoon of US Army Rangers (the Alamo Scouts) that fought the Japanese in New Guinea, and landed ahead of the main force in Luzon to help liberate American prisoners from the Japanese POW camp at Cabanatuan.

This is a photo of the officers of the First Filipino Infantry Regiment, United States Army, taken in San Francisco just before their return to the Philippines with General MacArthur's force. Their story is familiar to any student of the Pacific War: they participated in the "island hopping" campaign (also known as Operation Cartwheel) in the southwestern Pacific before reaching the Philippines. My father, who by then had become a Lieutenant, led a platoon of US Army Rangers (the Alamo Scouts) that fought the Japanese in New Guinea, and landed ahead of the main force in Luzon to help liberate American prisoners from the Japanese POW camp at Cabanatuan.

This story has become part of the narrative of the joint Filipino-American struggle to liberate the Philippines from Japanese rule. It is a key component of a shared history between the United States and the Philippines that continues to be upheld today.

This story has become part of the narrative of the joint Filipino-American struggle to liberate the Philippines from Japanese rule. It is a key component of a shared history between the United States and the Philippines that continues to be upheld today.

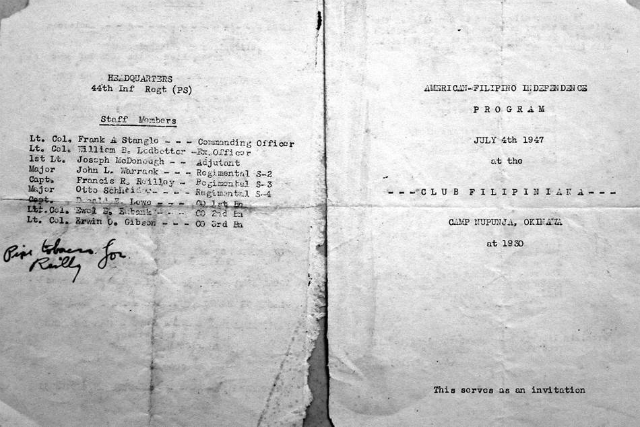

We get a glimpse of this shared history in this mimeographed invitation to the celebration, by the 44th Filipino Infantry Regiment in Okinawa, of the "American-Filipino Independence" on July 4, 1947.

Here, we notice that American and Philippine independence are jointly celebrated, with songs and the national anthems of both countries included in the program. This is not simply because of a coincidence in the date, but because Philippine independence was understood as the culmination of US tutelage: the adulthood of a daughter Republic of the American father, and the bond formed between Filipino pupil and American tutor in the common struggle against the Japanese enemy.

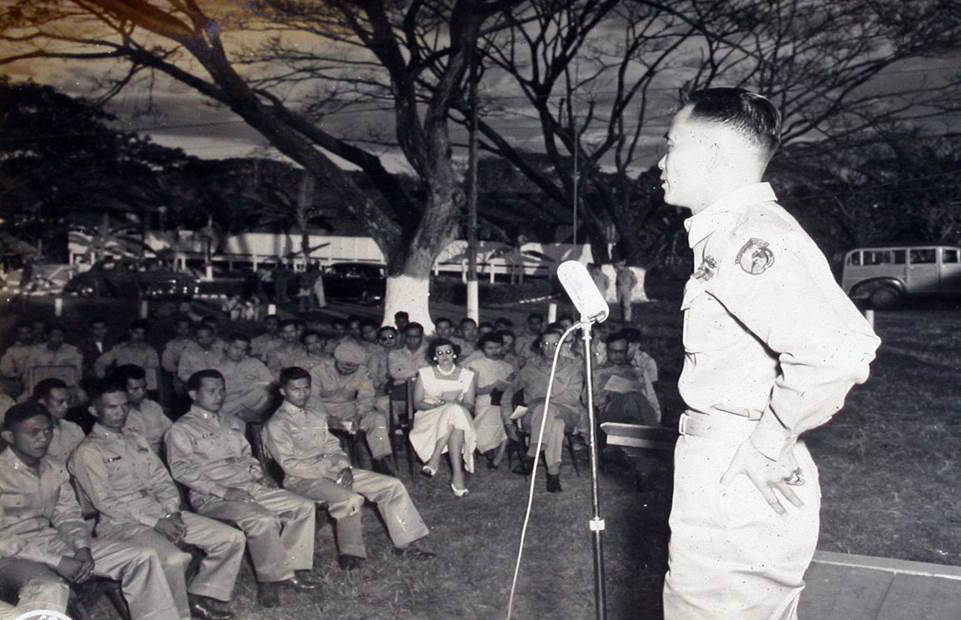

My father was offered American citizenship after the war, which he turned down to become an officer in the army of the newly-independent republic. In this photograph, now a Major, he is addressing the first graduates of the Scout Ranger Training Unit. Note the presence, in the center, of an American officer and his wife in the audience. Even in his battles against the Communists, Ileto was guided by American advisers and he embodied America's presence even after the Philippines became an independent country in 1946.

My father was offered American citizenship after the war, which he turned down to become an officer in the army of the newly-independent republic. In this photograph, now a Major, he is addressing the first graduates of the Scout Ranger Training Unit. Note the presence, in the center, of an American officer and his wife in the audience. Even in his battles against the Communists, Ileto was guided by American advisers and he embodied America's presence even after the Philippines became an independent country in 1946.

The shared history of their joint struggle is made possible, or at least made easier to accept, if it is accompanied by the forgetting of another struggle forty years earlier. My father, for example, did not believe that the Philippine-American War was a serious war; he even brushed it off as anti-American propaganda by the communists. It is not surprising that he didn't even know his father had been involved.

In the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, among the captured insurgent records, I found a letter in Tagalog that my grandfather, Francisco Ileto, wrote in 1900 to General Isidoro Torres (1866-1928), commander of the Filipino resistance forces in Bulacan. It states, among other things, that he is at the service of the General. However, the Americans intercepted this letter and labeled Francisco a spy for the insurgents.

At the time he wrote this letter, my grandfather was a citizen of the Republic who joined the resistance against US occupation—a fact he did not share with his children. This was a choice made by many of his generation who were eager to succeed in the new American order. As such, my grandfather became a mathematics teacher in the colonial public school system.

Naturally, my father was extremely surprised, even shocked, to see the document I had discovered in the Archives proving that his father had been a spy who resisted the American invasion back in 1900. For my father, the Philippine-American War was a non-event. The American educational system had produced a historiography that induced its forgetting. This helped to bind Filipinos to their American tutors and was the key to their ongoing "special relationship."

- Next Page

- continues