Now, what about my mother? The story of my mother's family tells us a different narrative. Here, in December 1946, my mother Olga is holding me in the backdrop of the Manila Hotel, which became the headquarters of General MacArthur during the Commonwealth period from 1938 to 1941. My mother did not experience the war because she was a student in the United States, where she met my father.

Now, what about my mother? The story of my mother's family tells us a different narrative. Here, in December 1946, my mother Olga is holding me in the backdrop of the Manila Hotel, which became the headquarters of General MacArthur during the Commonwealth period from 1938 to 1941. My mother did not experience the war because she was a student in the United States, where she met my father.

My mother's older sister, Lyda Clemeña, was married to a dashing guerrilla officer Vicente Dinglasan. Having lost her husband to the Kempeitai secret police, however, Aunt Lyda began writing poems about her love for her husband, his patriotism, and her search for his grave, as if to fill in the immense void she had suffered. She wrote about the absurdity of war, but, interestingly, there is no hatred of the Japanese enemy in her poems.

This may perhaps be due to my maternal grandfather's position during the war. In this photo, my grandfather Engracio stands on the far right. To his right is Ramon Magsaysay (1907-1957) who had just been nominated as presidential candidate by the man in the center, José Paciano Laurel (1891-1959) who will reappear later in my talk.

This may perhaps be due to my maternal grandfather's position during the war. In this photo, my grandfather Engracio stands on the far right. To his right is Ramon Magsaysay (1907-1957) who had just been nominated as presidential candidate by the man in the center, José Paciano Laurel (1891-1959) who will reappear later in my talk.

Lolo Engracio [Grandpa Engracio] was a political ally of Laurel; they studied law together at the University of the Philippines and were active members of the Nacionalista Party. My grandfather was a good lawyer. He was, however, a poor politician and thus his career led him no further than becoming a Congressman in Manila, while his friend Laurel rose much higher and became the third President of the Republic [first President of the Japanese-sponsored Philippine Republic].

In 1943, my grandfather supported Laurel's government, of course, but—like my paternal grandfather, Francisco—he remained quiet about his wartime experience. Perhaps he was afraid of being identified as a Japanese collaborator because of his closeness to Laurel, or even because his brother-in-law, Augusto Ongsiako, received his medical training at the Tokyo Imperial University in the 1930s.

In addition to the political side, Lolo Engracio's ties with Japan consisted also of the personal involvement of his much younger sister, Purificacion Clemeña, whom I called Lola Nene [Grandma Nene]. In an interview with her in 1999, she told me about the one man in her life whom she was engaged to marry.

The man in the picture, whose name I do not know, was a Japanese officer stationed in the Philippines. They fell in love during the war and, having cultivated their love through a long correspondence, they became engaged after the end of the war. That's when Lola Nene traveled overseas for the first and only time to meet her fiancé's family in Japan.

The man in the picture, whose name I do not know, was a Japanese officer stationed in the Philippines. They fell in love during the war and, having cultivated their love through a long correspondence, they became engaged after the end of the war. That's when Lola Nene traveled overseas for the first and only time to meet her fiancé's family in Japan.

Despite their love, however, Lola Nene said it was just too complicated for a former Japanese officer to move to the Philippines. For Nene to move to Japan would have been worse as assimilation was particularly difficult in those times. Besides, she was taking care of Aunt Lyda's [her niece's] two children whose father [Vicente] had been killed by the Japanese Kempeitai. So it was impossible to leave them behind.

And so, in this history of my mother's family, Japan is situated quite differently.

As I was growing up, I had been bombarded by the media and elders with stories of atrocities by the Japanese: Japan was the enemy; the United States was friend, ally, and liberator. That was the dominant understanding. Travel, however, quickly dissolved these fears.

Seeing Japan and the United States in a Different Light

By the time I visited Japan, the country was no longer the enemy. Having hosted the Olympic Games in 1964, it had evolved into a so-called bastion of the free world, emerging as an industrial powerhouse. I was eighteen at that time. Naturally, I visited the usual tourist sites—Tokyo Tower, Nikko, Hakone, and Akihabara. Although technology and engineering were what originally attracted me to Japan—my involvement in amateur radio communication, for instance, brought me in touch with similar hobbyists in Japan—I became more interested in its culture and history, and, by extension, the culture and history of Asia.

Changing my major from Pre-Engineering, I graduated with a diploma in Humanities in 1967 and got a scholarship to pursue my MA and PhD degrees in Southeast Asian history and anthropology at Cornell University. Considering the particular year and time, I could not avoid being influenced by the anti-Vietnam War movement that was raging in the United States at that time.

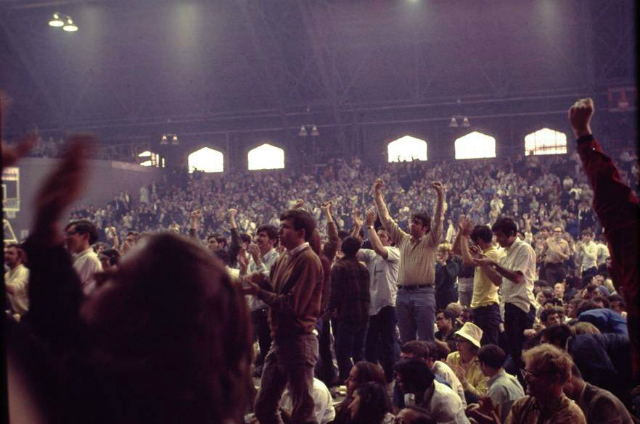

This is a photograph I took at an antiwar rally in the Cornell gymnasium in 1969. Like many of my generation, the antiwar movement from 1968 to 1974 had a profound effect on my outlook. Only with my involvement in the antiwar movement did I come to realize that the Philippines was the "First Vietnam."*4 My experience of the United States in the late '60s gave me a new understanding of the country that was missing in my education at the Ateneo de Manila University. The United States was not just the benevolent father who gave peace and democracy to the Philippines, but also a violent imperial and colonial power. This was the time when I became deeply interested in the Philippine-American War.

This is a photograph I took at an antiwar rally in the Cornell gymnasium in 1969. Like many of my generation, the antiwar movement from 1968 to 1974 had a profound effect on my outlook. Only with my involvement in the antiwar movement did I come to realize that the Philippines was the "First Vietnam."*4 My experience of the United States in the late '60s gave me a new understanding of the country that was missing in my education at the Ateneo de Manila University. The United States was not just the benevolent father who gave peace and democracy to the Philippines, but also a violent imperial and colonial power. This was the time when I became deeply interested in the Philippine-American War.

*4 The terminology is from Luzviminda Francisco's article, "The First Vietnam: The Philippine-American War, 1899-1902," The Philippines: End of an Illusion 2, no. 2 (1973): 106-145.

One of the notices posted during a student demonstration at Cornell read,

Carpenter Hall is a liberated zone-re-named GIAP-CABRAL HALL, named after Vo Nguyen Giap, victor of Dien Bien Phu, Minister of Defense of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, and Amilcar Cabral, leader of the liberation forces of Guinea-Bissau.*5

*5 From a notice on a window at Cornell University, 1972.

Both figures represented Communism, the official enemy of the Philippine-American-Japanese alliance of the Cold War era. However, the notice names these so-called official enemies as the unofficial heroes of the students. The shared history operating in this case is contrary to that found at the official level. What did the Vietnamese, Chinese, Blacks, Africans, Filipinos, and Japanese students share here?—the experience of being at the receiving end of American power.

My greatest discovery in the 1970s was a certain Filipino exile in Yokohama, General Artemio Ricarte (1866-1945). Artemio Ricarte was a veteran of the Philippine Revolution and Philippine-American War who had refused to take the United States Oath of Allegiance and thus had lived in exile in Yokohama from 1915 and returned to the Philippines in 1942 on a Japanese naval vessel. He gave a rousing speech upon his return, which was published in Tagalog and Spanish. It began,

Beloved Youth of my Country: It was about forty years ago when your fathers and elders were young people like you. I was together with them in the war against the Americans.... In the end, we were defeated in battle, not because we lacked bravery or courage, but because we lacked weapons. They surrendered against their will to the American army.*6

*6 Author's translation of Artemio Ricarte, Sa Mga Kabataang Filipino [To the Filipino Youth], Manila, 1942.

In essence, Ricarte was pointing to the forgetting of the sufferings of the Filipinos during the Philippine-American War. Why, he asked, do the youth remember the death and destruction during the revolution against Spain, but not during the war against with the United States? The answer, for him, was American colonial education: it had fostered the remembering of Spanish cruelties but the forgetting of the similar cruelties inflicted by the United States Army. Thus, the United States as the Philippine's ally could become the dominant narrative.

I only learned about Ricarte and the "forgetting" of the Philippine-American War in the late 1960s, but it was a decisive moment for me to begin questioning the historical basis for the "special relationship" between the United States and the Philippines.

- Next Page

- The Significance of 1956