ASIA HUNDREDS is a series of interviews and conference presentations by professionals with whom the Japan Foundation Asia Center works through its many cultural projects.

By sharing the words of key figures in the arts and cultures in both English and Japanese and archiving the "present" moments of Asia, we hope to further generate cultural exchange within and among the regions.

Provoking the Audience

Atsuko Hisano (hereinafter Hisano): I have seen two of your dances; one is Eyes Open. Eyes Closed. (a.k.a. Traitriot) (hereinafter Traitriot) held at the International Theatre Festival of Kerala, India, and Singapore International Festival of Arts in 2015, and the other is Passport Blessing Ceremony (hereinafter Passport) which I believe was a response to the Natsuko Tezuka's Dance Archive Boxes @ TPAM2016 at Performing Arts Meeting in Yokohama 2016 (hereinafter TPAM 2016). *1 These works, I think, involved current social and political issues in a very interesting way. In your profile, it said that you are interested in the body as a "political provocateur." Can you please elaborate on what you mean?

Venuri Perera (hereinafter Venuri): It was someone else who first described my work in those words actually, I think it was for the program of Tanztage, Berlin.

I want to provoke the audience; to encourage those who simply comply with the existing society and authority into questioning it. In Sri Lanka, performing artists had to submit their text or script to the censor board for approval if you were doing a ticketed show. So with words, there were limitations in what one could do. But I realized that with dance, one could be subversive without being censored. Although the content may be anti-authoritarian, the physical articulations of the body cannot be submitted in the script.

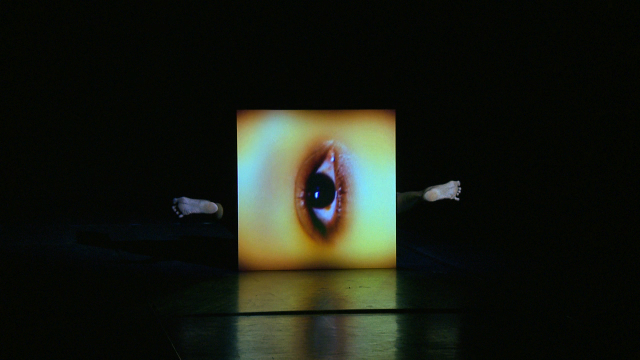

Traitriot questions blind and violent patriotism and implicates the audience by asking them to open and close their eyes throughout the piece. This to me is now unfortunately relevant not just to Sri Lanka, but in many parts of the globe where right wing nationalism is rising up.

Eyes Open. Eyes Closed. (a.k.a. Traitriot) Photo: Tuckys photography

Eyes Open. Eyes Closed. (a.k.a. Traitriot) Photo: Walter Bickmann

Passport is on the theme of national and legal identities that are imposed and/or "gifted" to us via the nation states, and questions the specific socio-political hierarchies that are determined within the global community. People have come to accept highly degrading processes to get access into a country and hierarchies as normal or are simply unaware of them if you are from a nation with a powerful passport. Separating the audience according to their citizenship in the beginning, and asking a German or Swedish citizen to bless me and my passport I hope questions the absurdity of it.

Passport Blessing Ceremony Photo: Kevin Lee

Hisano: What triggered your awareness of the need to question society?

Venuri: Most of my friends and family friends who I am surrounded by happen to be human rights lawyers, activists, journalists and artists. So I guess this awareness was kind of always there. But after many years of living abroad, returning to Sri Lankan society maybe made me question it more. The 30 year old Civil war had just ended, but the lack of accountability and a reconciliation process was alarming. There was a large number of displaced Tamil *2 civilians living in camps with horrible conditions. Increasingly disturbing incidents like disappearances of journalists and human rights workers became the norm. Some visual artists, and theatre makers were very much engaged with what was going on in the country, making relevant works, but not dance makers. I wanted this to change. I do think that this is one of the roles of artists, especially in a context mine, to question the status quo, question authority.

Living away from Sri Lanka, I had also got quite used to traveling and doing things by myself, but coming back made me remember how annoying simple things like walking on the road was, as a woman. The inherent patriarchy in society became more apparent to me. I am aware of the privilege I have as an English speaking middle class woman from Colombo and that I can raise a voice about certain things without too much repercussion except maybe to my reputation! And the older you get the less you care about what society thinks and says about you, which gives you the freedom to challenge the norms.

Photo: Naoaki Yamamoto

Hisano: Can you tell us about your other works and in what contexts they were made?

Venuri: My first solo Abhinskramanaya was created during my year at Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Dance and Music (hereinafter Laban Centre) in London. This was in a sense personal, depicting the internal struggle during the moment of departure from the known and revered (traditional dance) to the realm of the new and unfamiliar. My classical training was a lot highly technical abstract movement so my reaction to find meaning in movement and move only when completely necessary. I was struggling a lot with choreography and making the piece and really felt I wasn't creative at all. So when I received the award for choreography for that year at Laban, I was quite shocked. I remember my teacher wrote in my evaluation 'trust your choreographic voice'. In a way that gave me some confidence to even think about creating works in the future.

My second short solo, Soldier, was something I created for Resolutions!, a platform for young choreographers at The Place, London. Conceptualized by Christopher Engdahl, another young choreographer and I created two short works, responding to each other's existing solo works. Watching his solo, although it was unintentional, I kept seeing images of war. At first I was surprised, because I grew up in Colombo, rather in a bubble and largely not directly affected by the conflict. But in the end, it is in all our psyches, it had been going on from the time I was born, it's what we heard about on the news. Checkpoints with soldiers on the streets and the occasional bomb going off in the capital was normal.

After I returned from London, I started working in a local NGO that specialized in psychosocial work with survivors of torture and trauma. During this time I entered the post war zone in the North and East for the first time in 2009, immediately after the conflict ended. I visited the displaced community, in the capacity of a psychologist. I met people affected by the conflict and witnessed their plight. These experiences had a profound effect on me. My mother's friend, Kumari who had worked and lived with the Tamil community in the displaced camps in the East of Sri Lanka wrote a book of poetry, For Those Who Haven't Heard, in Sinhalese. When I heard Kumari reading her poetry, written after her experiences and the stories told to her by various individuals, it resonated with the accounts I heard during my visits. I really felt she was giving a voice to the voiceless. I worked with her and her poetry to create Thalattu (lullaby) for the second edition of the Dance Platform in 2013 which was curated by Ong Keng Sen. A narrative of the mothers who lost their children is what was emerged during this process.

Kesel Maduwa, and was triggered by the Buddhist monks led violent attacks and hate speeches against the Muslim minority community that started taking place in 2014. Recently, especially after the end of the 30 year old conflict, national identity and its (re)construction has flared up again rather violently. In Sri Lanka, monks are of a high social position and even the police cannot interfere with them. Being a Buddhist and also Sinhalese *3 , I was so ashamed and angry of these incidents. I was commissioned to do the opening piece for 'Colomboscope' festival, with the theme 'Making History' in 2014, I used this opportunity to create this work. In this piece, I look at religious and racial extremism as fringe insanity creeping into the core of society that needs to be exorcised with this 'ritual'. I worked again with Kumari to create the satirical texts for the work.

Kesel Maduwa Photo: Isuru Perera

Dance, Theatre, and the Psychologist

Hisano: In the pieces that I have seen, I felt that you successfully created a relaxed atmosphere by talking directly to the audience. I also liked your sense of humor. Do you think that may have something to do with the fact that you studied and have a degree in psychology?

Venuri: I'm not sure if it has to do with studying psychology, or more to do with the experience of being on stage and also working in theatre. I realized that most of my works tended to be dark and minimalistic although I think I am generally quite a bubbly person! The speaking was for me a solution to this dilemma I had about my 'dominant self' being absent in my pieces, and to bring in a bit of lightness. In Traitriot, when I speak to the audience, it's primarily because I have to give them instructions which they have to follow during the piece. Also, it's important for the audience to feel invited, and relaxed, so later when the piece starts getting violent or grotesque, there is a switch in their experience. The piece is about control and manipulation, so I am manipulating the audience's expectation by being nice in the beginning.

Passport is in a way directly personal, and I explain the reason for this personal ritual to the audience in the beginning. Again, the ceremony itself goes into an uncomfortable space and I like to think that the audience is taken on a sort of experiential journey. For me, the experience of the audience has become very important.

Hisano: How did you relate your studies in psychology with dance?

Venuri: I had been brought up with a strong sense that I had to serve society. I had no intention of becoming a choreographer or performer professionally. But I still wanted to work with dance and be 'useful', so I thought dance therapy was the answer. So in order to prepare myself, I studied psychology. I later went to Laban only because they had a Post Graduate Certificate: Dance in the Community, where I learnt 'Community Dance'. Here I learnt the difference between movement therapy and therapeutic movement and how to work with dance in marginalized communities.

Photo: Naoaki Yamamoto

I was attracted towards certain types of performance projects, and I guess my education and interest in psychology made people consider me for them. For example, I was facilitator, choreographer and performer in a theatre project for the Edinburgh International Festival 2005 and 2006, where we worked with children affected by the Asian Tsunami and Civil Conflict in the South and East of the country. I was also a dancer in a project 'Upheaval' with German mixed abled dance company DIN A 13, where three of the dancers were ex- soldiers who had been caught to land mines during the conflict.

The Turning Point: Encountering a Curator

Hisano: Then, there was a turning point?

Venuri: I changed my mind from wanting to become a dance therapist to working in dance as a performer and creator, because of my experiences at Laban. But after I came home in 2009, I felt lost, not really fitting in to the existing scene and started working full time as a psychologist in the local NGO. Although I learnt a lot, I was not really happy with the work there, as I felt the methods used were not making any long term impact with the communities we were working with, and as a young woman, it was impossible to change existing patriarchal structures.

In 2010, the director of the Goethe-Institut wanted to create a platform for independent dance, and invited Tang Fu Kuen from Singapore, to curate. I was asked to coordinate between the local dance community and Fu Kuen. At some point, he asked me to show him my own work, then insisted I perform at the Platform.

So, at the Colombo Dance Platform's first edition, I presented the two short solo pieces that I had made during my time in London. When Fu Kuen introduced me to the audience, he said something along the lines of, "Venuri Perera a former member of the Chitrasena Vajira Dance Company, starting off her career as an independent artist." I remember the moment when I heard that before going on stage and thinking, 'Is that what I'm doing?'. Eventually, over a period of a year, I stopped all full time work so I could work independently as much as possible. This has not been easy, as the 'independent dance' scene is almost nonexistent, there are times when there is no work and some projects don't pay at all. I work with theatre companies and recently found myself in performance art platforms. Many people back home still look at me incredulously when I tell them I am dancer (I only found the courage to do this recently) and that I don't have a job. Many don't understand why I do not even have my own dance school or company or even how I manage to travel with my work.

I really do believe that movement and performance can be a powerful transformative tool, and that mind and body are interconnected. I continue to work with creative and therapeutic movement in various contexts including reconciliation. Also, In Sri Lanka, the all night rituals were really psychosocial therapy, community healing and I guess going back to researching ritual is a way of connecting dance and psychology. In my current series of work I speak and move with one audience member at a time, in a very intimate situation, in complete darkness. The feedback I have been getting from the audience is that it is in many ways 'therapeutic' and my own experiences have been really transformative for me as a performer as well.

Photo: Naoaki Yamamoto

The Importance of the Dance Platform

Hisano: Does the dance platform play an important role in the dance scene in Colombo?

Venuri: I think it does, as it is the only platform for independent dance makers' to showcase smaller works. It's also a safe space to experiment and where subversive art could be shown. But the contemporary dance scene and experimental scene is very small, although I hope slowly growing. So though in the larger scale of things it may not seem as if it's playing a huge role, it's very important and essential. It has allowed for interesting collaborations to take place and not only dance makers, but anyone working with the body is included and so this sparks interesting conversations and perspectives. Usually there are discussions after performances so it also helps to build a critical participative audience.

Although it happens biannually, we have tried to have various events leading up to it like meetings with the community, workshops, film screenings and work in progress sharings. The previous two curator's Ong Keng Sen and Anna Wagner also contributed dramaturgically to the commissioned works. The last year we had a one week long dance camp where the selected makers shared their processes and initial concepts. We had mentors like Preethi Athreya and Shankar Venkateswaran from India to follow and guide the creative process as well. The problem is though, that it is hard to get people together when there is no public performance, so immediately after the platform, nothing really happens for another year or more.

Photo: Naoaki Yamamoto

*1 Dance Archive Boxes @ TPAM2016 was a project where artists themselves create a dance archive not for preservation but re-creation purposes. It was initiated by Ong Keng Sen, the artistic director of Theatre Works, Singapore, and was held in three cycles from 2014 to 2016. The Saison Foundation organized the first cycle where seven Japanese dance artists created the "dance archive boxes;" the second cycle was held as a program for the Singapore International Festival of Arts in which South Asian dancers re-created their pieces using the boxes made in the first cycle. And finally, the third cycle, directed by dance dramaturge Nanako Nakajima and held at TPAM 2016, featured reports on the project as well as demonstrations and symposia exploring the future possibilities of the project explored from new angles.

*2 The largest ethnic minority group that occupies approximately 15 percent of Sri Lanka's population (as of 2012) who live mainly in the northern and eastern regions of Sri Lanka and Tamil Nadu in South India and speaks the Tamil language.

*3 An ethnic group that occupies approximately 75 percent of Sri Lanka's population (as of 2012). The term "Sinhala" means "descendants of lion."

- Next Page

- The Situation of Sri Lankan Dance