Why Theater?

Fujioka: Why did you choose to do theater and how did you start? Did your family accept this as your career choice?

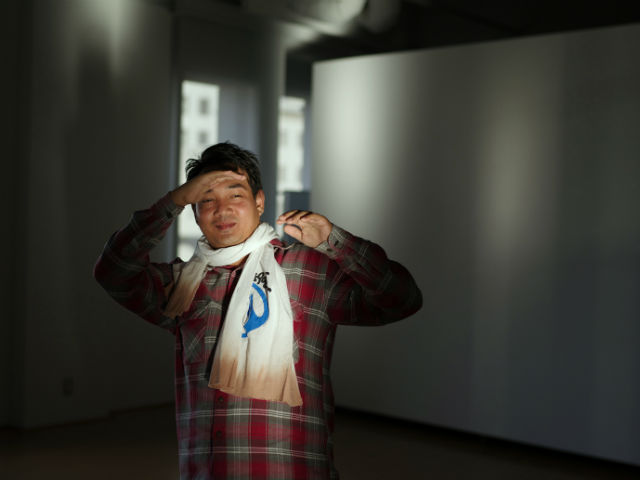

Soe Moe: I like drama and theater because it's closely tied to people. And another thing is that I'm not alone. I don't want to be lonely, and theater provides me with so many friends and colleagues.

Fujioka: Like a community?

Soe Moe: Yes. And you can easily convey messages to the community through theater and drama, too.

Fujioka: And your parents agreed?

Soe Moe: They don't understand [laughs]. Our conversation goes, "What are you doing?" "I'm playing in a drama." "What?" But they at least know that I am a drama teacher.

Thila: My maternal grandfather is actually Khin Maung Nyunt, a very famous stage and cinema actor in Myanmar of after World War II. He came here to Japan and edited one of his films, I think. That's what my mother told me. But after my mother's generation, nobody did the arts. When I was young, I wanted to be a singer; I really liked the arts. After I was released from prison, I chose theater. But nobody understood me; nobody. People who were in the arts just tried to get famous as a commercial business. They said, "You are a good actor, be a movie actor. Get into commercials and films." But I never did. Nobody understood. Not even my wife; she didn't understand until two years after our marriage.

It was only after 2010 or 2012 when people began to see our work and what we are doing. I think our recognition is growing. My wife now knows that I help the community. But my mother asks me, "Why are you doing this? You don't have any guarantee. You have no salary." Sometimes I don't have a job for three months so she'll say, "Why don't you work in an office and get a stable salary?" It would have been easy to go to the United States or somewhere else because I was a political prisoner. But I never did. My mother says, "Go to the United States, study, and start a new life." "Sorry ma."

I'm still really interested in Myanmar and working for the community. In my mind, the government has not changed. I know the situation very well, because I was in the revolution; I was involved in the [democracy] movement.

For example, before 2010 we were once collaborating with the Bond Street Theatre. We would travel outside Yangon to rural areas to perform. Sometimes the police came and they would say, "You cannot perform here. Go back to Yangon." We said, "Ok, we'll go to another place, a tourist spot." We stayed away for one night, but the next morning we went to another rural area and continued our performance. We took the risk and did our work. I really wanted to continue that kind of work so I stayed in Myanmar. Nobody understood that then. Nowadays, they can see my work, and the government is changing. Well, not all entirely, but slowly.

Fujioka: People overseas think that things have changed overnight. But change doesn't happen so fast.

Thila: Now people around me are starting to understand what I'm doing. Nevertheless, the traditional theater world thinks that we are not "professional" because we perform outdoors and for free. Another challenge for us is to be a registered, legalized theater troupe, because otherwise the traditional theater association won't recognize us. When we do a performance, we need to speak with the local authorities who ask for our legal status, just to make it difficult for us to work. We can manage, but not officially.

Soe Moe: Nowadays, although the restrictions against freedom of speech have become less strict, if you want to do a performance, you still need to get permission from the government. That's why we need a legal status.

Democracy and the Art Movement

Fujioka: I'm curious about the connection between democracy and the performance art movement in Myanmar.

Thila: There is a strong connection. At our performances, the audience needs to think critically. This is a very important mechanism of democratization. So we are nurturing people to think critically. This is why the contemporary arts movement is very important for our country's democratization.

Intellectual elites can already think critically, but the local people don't have a chance to do so because they are sunk in trying to survive their daily lives. When we bring our performance to them, we are trying to encourage them to question things in a friendly way. We believe in the people, that they can think [for themselves]. We don't tell them to think, we empower them to think.

Fujioka: After Cyclone Nargis, you did some work with the survivors. How did performing arts or drama help communities recover? In Japan, there was a huge earthquake in 2011. I'm interested in how art can help victims of a catastrophe.

Soe Moe: Some organizations worked with all community members, but our group focused on children and we made a psycho-social support program for them. To help them come to terms with their trauma, to heal psychologically, and to improve their well-being. We ran the program for almost every day during the course of nine months.

Thila: Artists went and stayed in the area, visiting villages every day and holding art classes. Like using drama in playing games or making a performance, collaborating with our comedians.

Soe Moe: Traditional standup comedians.

Thila: Other times, some NGOs invited us to promote health issues. We would put on a performance that deals with dengue fever, diarrhea, promoting washing your hands, what you should drink if you have diarrhea et cetera; that kind of edu-tainment. It's part education and part entertainment. And after that program, we would do a performance there.

Fujioka: What is the situation in that area now after Nargis?

Thila: Now, psychologically, they have recovered. But the paddy fields were flooded with salty water so they cannot plant rice anymore. I think it's still difficult for them socially.

Technical Support and Critical Thinking

Thila: From overseas, we do want them to invest in us, but we also need their cultural support. As for theater staff, we need technical people: for the lighting, sound, and stage production et cetera. In Myanmar right now, we just don't have those: one staff member is the actor, stage manager, costume, makeup artist; he does everything. I'm a director but I also do everything else. That's how we are working now, but we cannot survive like this for very long. We need technicians. If we could at least nurture a market, I think we would be able to attract young people to work in the industry.

People think you can't earn money in the arts. But you can make a living out of it. If we could create a market and industry that is not only for making profit or for commercial purposes, we can continue working in the arts for the community, and, maybe, in a few years, we can generate the money for growing a team. Money is also important to a certain extent. That's why, we welcome investors. Please come and invest in the art market.

Fujioka: I was surprised that so many people have smartphones in Yangon. A lot of information is rushing in from the world now.

Thila: Yes, that's why you need critical thinking; it is very, very important. It could be really dangerous for our country without it. The military dictatorship has killed our thinking, and that's why I would say the war has not ended yet. There's lots of information that is accessible to us now so it is really difficult to control it right now. That's why we need to nurture and practice critical thinking, especially among the young people. For my generation, it is ok―we'll pass soon―but it is crucial for the next generation. Right now they're just copying and very easily accepting everything they see and hear. Consumerism is being imported now, and that's a big issue, too.

Fujioka: Are Myanmar values or identity important in the arts?

Thila: Yes, I believe we have to protect some of the identity of Myanmar. Because as human beings, we all have our own identities, right? I do believe in globalization and modernization, but I also believe in local identity. I don't know which ones we should keep and which ones we should let go of. But I believe the local identity is something very valuable to us. For example, in our family, my mother is very much involved in our lives. Even at my age, she sometimes crosses the line into my personal life, which is something I sometimes want to get away from.

Fujioka: It's so Asian.

Thila: Yes, it is. In this modern world where people live on their phones, I can avoid her in a way. But sometimes I really like her involvement because I don't feel alone. I know that, at least, my mother is concerned about me; that feeling, of having emotional support, is really good for me. I really want to maintain that. I think I want to provide the same support for my own daughter, too, but I know where to draw that line. I don't think I'll cross my daughter's line.

Parents will always care for their children; even if you are eighteen or over forty, you will always be their child. That's an example of our culture I really want to keep. It's our identity, our Myanmar identity.

Soe Moe: I think that sometimes we need to promote our cultural identity to keep it. But how can we promote Myanmar identity? My idea is to collaborate with other cultures, artists, and/or art forms. I think we can better see the value of our culture when we promote them.

Thila: We are working globally; we collaborate with international artists. I agree that in a collaboration neither party loses their identities; we create a new identity.

Last month, we collaborated with the Bond Street Theatre. We created a work together based on Volpone, a play written by Ben Jonson. Although it is written by an Englishman, we tell the story including some current issues in Myanmar. In that way, we are finding a new identity.

In the original story, there is a rich man who is bad and greedy. He pretends he is ill and will die soon, but he doesn't have an heir. That's why other greedy men come with presents to have their names included in his will. There are three characters; a lawyer, a veteran, and a real estate broker. In the end, the rich man's servant inherits all the property. That's the original play, but we added local insights and we also cut the play after an hour.

Fujioka: Then you start your interaction with the audience, I see. And the themes refer to cronyism and inequality in Myanmar society. Finally, how is this trip to Japan for you?

Soe Moe: This was my first time to visit Japan. Yesterday we watched two performance shows. I learned, through observation, some ideas about performance―how to make the set, the lighting, up-to-date technology, and also how to work with and in festivals. In the next few days I hope to meet more people and see different kinds of performances from many countries and cultures.

Thila: TPAM is a new experience for us. We are still learning; we learned that there actually is a performance arts industry, how they are working internationally, and especially how we need to talk to festival members and directors. We are focusing on local performances now, but we really want to take our performances outside of Myanmar. We believe that we have a rich performance culture to show to the world.

Fujioka: Certainly, yes. I hope that your networking will bear fruit for the future.

At the YCC Yokohama Creativecity Center, on February 13, 2017

Interviewer: Asako Fujioka

International film festival organizer and distributor. Worked with Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival in Japan from 1993 on as Coordinator, Director, and now on the Board of Directors. Established the New Asian Currents program, a collection of films and videos by emerging documentarists from around Asia during the years 1995 – 2003. Organizer of film workshops with Asian filmmakers from 2009 on. Selection committee and advisor for Busan International Film Festival's Asian Network of Documentary (AND) Fund since 2006. Sometime distributor of Asian documentaries in Japan, and Japanese documentaries overseas. Joined organizing committee of international co-production forum Tokyo Docs in 2016.

Photo: Naoaki Yamamoto