Sarah Monica (hereinafter Sarah): How many literary festivals are held in Indonesia on a local and international scale?

Yusi Avianto Pareanom (hereinafter Yusi): The word "festival" is a flexible term, widely used for all types of activities. It is difficult to calculate the number because very few occur consistently every year. Most are held sporadically. Very often, those with a passion, interest, and love for literature organize the festivals. Then, once aware of the difficulty, they back off. Most festivals are singular events.

The international festivals that still run are the Ubud Writers and Readers Festival (UWRF), the Makassar International Writers Festival (MIWF), the Jakarta International Literary Festival (JILF), the Literature and Ideas Festival Salihara (LIFEs), and the Borobudur Writers and Cultural Festival (BWCF). As far as local festivals, Patjar Merah, initiated by Windy Ariestanty and Irwan Bajang, our partners, also fills the book bazaar. It is a traveling literacy festival. Specifically, it is not a literature festival but a literacy festival, which moves from city to city for equal access to reading. Interestingly, they finance this festival themselves (self-sustainable) with a book bazaar at friendly prices. They also use unusual venues to exhibit. In Yogyakarta, they use warehouses. In Malang, the stalled Misbar cinema. In Semarang, in the Old City. They planned to move around to many sites, but, unfortunately, the pandemic interfered again. Apart from the book bazaar, they also feature many writers, musicians, and filmmakers to perform.

Kalimantan is the site of another local festival named Aruh Sastra. Aruh is a local term meaning kenduri in Indonesian or festivity. Therefore, by using the concept of kenduri, they organize the festival by moving from one place to another, expanding the festivity spirit. Like Patjar Merah, we can also find this kind of festival in Sulawesi and Bintan. Unfortunately, almost all of the festivals are affected by the pandemic. No official data exists, but there are dozens. Consistent annual festivals, there are, maybe, less than ten.

Sarah: What made the literature festival flourish in Indonesia?

Yusi: What makes people look forward to the festivals, I think, is the strong festival identity. Some festivals are more like writer meetings. One festival with a strong identity is the MIWF. Its mission is to introduce writers and repertoire from Eastern Indonesia. Initially, it focused specifically on Sulawesi, but now it has expanded.

JILF is a festival that brings together writers from the Southern Hemisphere. So, that identity will be the basis of each implementation. Simply stated, even if JILF has a lot of money, JILF will not invite writers like J.K. Rowling because it is a forum for exchanging ideas between fellow writers from the Southern Hemisphere. The spirit is Asia-Africa plus Latin America, in the end. UWRF was intentionally created to strengthen the Balinese economy after the Bali bombings. The tourism element is powerful there. The literary elements in these festivals are unique, as are the celebrations. When people come to a festival, they know the individual characteristics and what to expect.

Sarah: What is the biggest challenge in organizing a literature festival based on the experiences at JILF?

Yusi: Starting something new. Jakarta is no stranger to festivals, but the Jakarta Arts Council (JILF organizer) has never had one. The main challenge is maintaining stamina. It is easier to find additional funds if you are already known.

We went from one embassy to another in search of support. We approached several companies, even the writers we invited. Not all writers were willing to join because they were unfamiliar with the JILF festival. After the festival, many wrote to me directly, saying they regretted their decision not to participate, and explained why they did not come to JILF before. We had to convince the Ministry of Education and Culture and the Governor of Jakarta that JILF adds significant value to Jakarta, making it prestigious in the eyes of literary world. In the end, we sold the strength of the festival concept and the organizer's reputation.

Sarah: What is the biggest challenge for other festivals that are already known and run consistently, such as the BWCF, MIWF, or UWRF?

Yusi: I cannot speak on their behalf, but from what is often discussed, fundraising is a significant problem every year. Maybe UWRF is more established because it has many partners. Other festivals are constrained by bureaucracy and are unsupported by local government. Additionally, when the organization depends too much on sponsors and is not independent, its fate will always be in jeopardy. The real challenge of a festival is to become financially independent. It is why I'm elated to see a festival like Patjar Merah make a serious effort to become independent from the start.

Sarah: Apart from the funding problems, is there anything else that prevents the festivals from surviving?

Yusi: Yes, organizational problems. Is the organization created for one-time-only or sustainable projects? If the organization is sustainable, there must be planning beyond a single year's implementation. We have to imagine the festival over the next five or ten years.

Interestingly, the term "amateur" comes from the word "love," and festival organizing is, indeed, started from love or passion. However, in practice, enthusiasm alone is not enough.

Sarah: The Covid-19 pandemic automatically hampers all activities, including festivals and other arts-based activities. Some venues hold festivals consistently and adjust. How has the literature festival adapted amid the pandemic? Have the events changed to online platforms?

Yusi: Yes, as far as I know, some have moved online, while others have halted. JILF and UWRF will be virtual events. MIWF took a break last year but returned this year as an online festival. Patjar Merah was an online festival last year, and this year the enthusiasm for it is still strong. Regarding the publishing sector, because I am also a publisher, the enthusiasm is excellent. Several small festivals were postponed. Keep in mind, the term "festival" comes from the word "festive" or "crowd." There is a big difference between online and offline events regarding direct interaction. When we participate online, we listen specifically to a one-topic discussion. When an event is offline and in-person, maybe we intend to come to one session, but other things or new encounters with people at the festival broaden our scope and make it fascinating. To summarize, the possibilities in offline events are far more numerous. For example, the opportunity to meet writers can develop into new activities and exciting directions. There are new ideas, new opportunities to explore. Online, the excitement is very different. I'm not saying it's not as important, but very different.

Sarah: What is the impact of the literature festival on literacy culture in Indonesia?

Yusi: It is a broad question. Each festival inspires visitors to create a festival in their respective locations. A festival followed by a bazaar will have a financial and beneficial impact on the literacy world and industry. But if you look at the common thread in every festival, there is an effort to introduce new, young writers. Whether in MIWF, UWRF, or JILF, there are always efforts to recognize writers who are considered "potential" by the curators and are not widely known. Through festivals with international embellishments, our work is increasingly recognized by the outside world, but it is still too early to measure the impact. If writers know each other and collaborate, there is more impact. I think the measurable impact is in the influence of the industry and its knowledge production.

JILF has substantial efforts in the knowledge production field. Every writer who attends JILF must write a paper because we want to generate knowledge production from this event –so that it is not just busy, happy, reading works. Borobudur Festival is also serious and prepares solid materials on culture, interfaith, etc. Even if I did not attend, I was able to gain knowledge from this festival. It is about more than just an annual event.

Sarah: Can you see that the festival also impacts reading interest?

Yusi: Regarding reading interest, it is, again, questionable. If it is said that Indonesia's population has a low interest in reading – what are the parameters? Every festival has crowds of visitors. In addition, book sale events, such as the Big Bad Wolf bazaar, are always crowded. Although some say that the visitors are only middle-class, the bazaar itself is twenty-four hours long. Why are people so eager to buy books that they purchase them in trollies? The problem is access, not low reading interest. It is a problem of uneven access to book resources.

Festivals like Patjar Merah prove that the premise of low reading interest among Indonesians is wrong. What is true is limited access to literacy. Books that can be easily accessed by friends in Java, especially in Jakarta, are difficult to obtain for those who live in East Indonesia or Kalimantan. Additionally, sending books isn't cheap. Sometimes, the shipping costs are more expensive than the book price. Festivals like Patjar Merah become an alternative way to bring books to readers.

If reading interest is low, why does every book bazaar event have tens of thousands of visitors coming to buy books? Furthermore, the buyers are not just university or high school students but housewives and working artisans. They are happy to buy books that they have not seen before.

Sarah: Do literature festivals influence the political and social conditions in Indonesia?

Yusi: We don't have a specific festival that addresses such things. We take all themes. Currently, there is too much information demanding our attention. Niche themes only attract those interested in discussing a particular subject. Can festivals move people en masse to do something related to social and political issues? I don't think so. You can change and inspire people or small groups. Just like the Patjar Merah festival in Malang has inspired friends from East Nusa Tenggara to organize similar events in Bajo. Significant changes always start from small ones, except in revolution.

Sarah: Do Indonesian social and political issues impact the organization of a literature festival?

Yusi: Yes. The political and social situation in the 80s and 90s produced a festival that addressed contextual literature. There was also a situation of religious excitement resulting from the Islamic Literature festival. But apart from inspiring, there are also obstacles. If you remember, some time ago, UWRF planned to hold a session themed on the left or the history of communism in Indonesia. In the end, it was banned. In Jakarta, another festival called "Kiri Jalan Terus (Left Going Ahead)" was prohibited, also, but not by the authorities, by religious groups. For example, mass organizations, such as Front Pembela Islam (FPI), once dissolved an event featuring a lesbian writer from Canada. Challenges arise when some community groups try to silence the expression of other community groups, in this case, the festival organizers. It is a serious matter.

Sarah: In light of the long pandemic, what is the prediction for future literature festivals in Indonesia?

Yusi: I am sure the festivals will run again when the pandemic ends. People yearn to meet and share, too. If anything, the pandemic has taught us to focus on the things that matter. Essentially, if the activities are not too impactful, we don't need to spend a lot of energy on them. Anything can happen in this pandemic situation. There is a lot of fuss at the festival. For example, why is A instead of B invited, or why is the theme A not B? There are always useless commotions, but I am optimistic about the future of festivals overall.

Sarah: Now let us go back to Jakarta International Literary Festival (JILF). How did it come together in the first place?

Yusi: JILF was held officially for the first time in 2019, but the seeds of the idea were already there two years before. Planning who should be in this organization was more important than when, where, and who to invite. After that, we worked out how much money we needed. It took this idea two years to come to fruition. At a festival, if you come just to read the work and leave, it is easy. But a solid and coherent event cannot be created by one head alone. We were lucky that our team was solid and assisted by many volunteers.

Sarah: How unfortunate that it only started in 2019, then was hit by the pandemic.

Yusi: In 2020, my friends and I contacted several other organizations that supported us. The preparations were done, and the quality of the featured writers was also becoming more awesome. Unfortunately, the festival could not be held according to plan. Although last year was held online through podcasts, we have to admit the excitement was different.

Sarah: How is the curation process at JILF? There must have been protests, as you mentioned earlier, because you included author A instead of author B.

Yusi: The JILF process is democratic. After deciding the festival identity, we agreed on the theme, programs, and symposium for each panel. The gender composition required balance. There have to be representatives from inside and outside the country. In addition, we also have to have a balanced representation from several groups. Each symposium theme is decided by consensus. Discussions for the daily sub-themes and speakers happen according to the issues raised. Once announced, if there are any comments or criticisms about the selected speakers, we consider them as input. Some themes may be considered "boring," but we think these themes can become a red thread between other sub-themes.

Sarah: How does a festival impact writers?

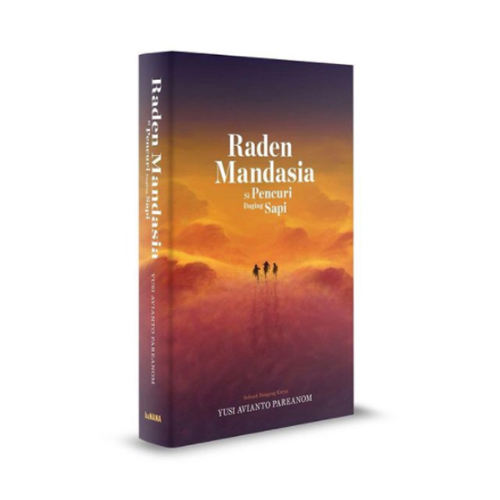

Yusi: Local writers tend to be scouted by publishers. If a book is published by the time a writer comes to the festival, it can sell even more copies. Writers get inspiration in new places. In an international context, we have not yet introduced Indonesian writers abroad. At JILF, we created a "Literary Agent" class because there are only three or four literary agents in Indonesia. Indeed, there are Indonesian books that have been sold abroad already. But the numbers are still small compared to the total number of books, as a whole.

Writers can learn a lot from a festival. Festivals are not only about celebrations. They are symposiums where an author's ideas are confronted or challenged by others. Regardless of agreeing or disagreeing with the idea, the process itself enriches the writer's knowledge if the writer is willing to learn. If the writer doesn't have a Prima Donna complex, they will learn a lot. Honestly, if a writer opens up to a cultural event like this, they inevitably get a humbling experience. They soon realize that "there are still many people much smarter than me, and I can learn a lot from those who are even younger." If one accepts such lessons, they emerge with richer insight after experiencing a festival.

There were many surprises at the festival. Like the experience at JILF 2019, we brought friends from Botswana. In Botswana, publishing a book is very difficult. Before a book gets published, they must first accept school textbooks or school storybook orders from the government. They must submit their work for selection many times before it gets published. In Botswana, publishing only 500 copies is considered a best-seller. It's an astonishing fact compared to us, who can even self-publish. We recognize we have privileges over those who live in Botswana. Such situations teach us to be grateful and appreciate what we take for granted.

Sarah: Does a festival make it easier for writers to sell their works?

Yusi: Yes, indeed. Moreover, with business logic, the price becomes cheaper. In addition, readers can also meet the author. However, festival book sales are not very big, only between ten to a thousand copies. In the context of book sales, the festival becomes a promotional event. This depends on how the festival organizers package it.

Sarah: At the festival, at least publishers can get to know writers whose works have the potential to be published, right? Do you target those writers?

Yusi: There are some festivals which published the works of young writers invited to the festival—writers who have published only one or two books or even none, but have published in the mass media. With books published by festivals such as the Ubud Writers and Readers Festival (UWRF) and the Makassar International Writers Festival (MIWF), publishers can evaluate if the potential writer is suitable for publication. It's what I meant by knowledge production from a festival.

Publishers usually hunt through many media, one of which is festivals. In addition, writers can receive a contract with a particular publisher or a writing competition from the Jakarta Arts Council. The winning works can be judged for publication. Right now, some bloggers get targeted by publishers, like those writing on Wattpad. Publishers target writers from there. It depends on the publisher and what kind of work they seek. At festivals, even though a publisher doesn't sign a new writer, they still make new friends. When their friendships go well, they can be a voluntary promotional agent for writers. Again, it depends on the quality of their work. Publishers will not risk their professional reputations by promoting mediocre work simply because they know the author.

Sarah: We are in the digital era. Today, it is easy to publish and sell books online. What are the challenges for the literature festival in facing this digital era?

Yusi: Instead of challenges, I think about how the festival can optimize the digital platform. Social media can generate crowds and prolong the excitement long after the festival. For example, teasers and event posters before the festival make people want to participate. It is how festival organizers take advantage of digital platforms to benefit the event. Even when the event is over, the festival excitement gets shared via social media. In my opinion, it is not a barrier. It is another tool that can strengthen the festival. Offline events offer some irreplaceable things, but online events have their advantages. For example, chatting via Zoom like we are doing now, despite an offline warmth that cannot be achieved in online platforms. Then again, my opinion is the voice of the analog generation and does not represent everyone.

Sarah: Are there any publishers that sell books only in digital format?

Yusi: Almost all publishers have a print and digital version. But here, in Indonesia, printed books outnumber digital books, at least at my publication and several other publications. Readers still enjoy holding books. Even though most sales happen through digital platforms, people still like physical books to show them off on social media, such as Instagram. These readers have a certain pride, especially if the book is not a mainstream book.

The rules of the game have changed since the advent of social media. In the past, people had to go to bookstores to get books. Now, there are many online resellers, and they also give discounts. One big difference is that space in bookstores is limited. Therefore, the shelf life of books on display is limited. If the book doesn't sell well, it will go to the warehouse. Some books need momentum to be liked by readers. Sometimes when a book is finally widely discussed, and people start to look for the books, it is no longer on the shelf. Now that we have social media platforms, the books in online bookstores are always there. With social media selling so many books, indie publisher benefit because their shelves are always stocked, unlike before.

Books do not need intermediaries through them, or they may have different intermediaries to reach readers. In the past, whether you liked it or not, the only intermediary was the big bookstores. So, yes, it is a game changer for the industry.

Now, community bookstores are starting to appear, and readers usually like to go to new venues. It's the same reason why people enjoy coming to festivals. For young people, in addition to having the opportunity to meet the author and also get a book, the desire to show the world that "I am present at this important event" is unavoidable. When someone comes to a literary festival where the idolized person is, of course, they feel a sense of pride. They go for FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out). The encouragement, although artificial, is still critical because it enlivens the festival and sells books. Even if their initial interest is superficial, in time, I'm sure these people will become serious readers.

Sarah: Is that a criticism of young people who only want to attend festivals?

Yusi: Well, I am just happy. The important thing is to get to the festival first. I believe young people will also become open to reading by joining discussions. They will definitely start to get intrigued. Many fascinating things can inspire. You will be surprised to know that the festival organized by Haru Publishers, promoters of East Asian Literature, offers a deep knowledge of works from that part of the world, not only the names of mainstream writers like MURAKAMI Haruki. People can be happy about the festival if they have access to it. Equitable access is indeed a common duty, although people have different interests. Whether they like East Asian Literature, West European, or Latin American literature, it's up to you.

Sarah: In closing, what are your future hopes for the Indonesian literature festival?

Yusi: Well, what I hope for is normative and cliché. I want to see more diverse festivals held at many points in Indonesia with consistent and professional implementation. In addition, I would like to see more knowledge production from these festivals. If festivals are produced continuously, we can address your previous question on the impact of festivals on social and political environments.