ASIA HUNDREDS is a series of interviews and conference presentations by professionals with whom the Japan Foundation Asia Center works through its many cultural projects.

By sharing the words of key figures in the arts and cultures in both English and Japanese and archiving the "present" moments of Asia, we hope to further generate cultural exchange within and among the regions.

Nationalism Overdrive in "SG50" Singapore

―How was your trip to Yokohama?

Alfian Sa'at: It was very interesting. It is my first time there — I had never thought of going there just for a holiday. Whenever I visit a country, I always want to visit local artists to gain insights that tour guides cannot offer. This time, I had the chance to meet and talk with many of them which was fantastic. It was also lovely that I saw a lot of Southeast Asian artists at TPAM, including artists from Malaysia's Five Arts Centre who came to stage their show, Baling. It was one of my favorite performances at this year's TPAM. I felt a Malaysian-Singaporean pride.

―The relationship between Malaysia and Singapore is quite unique. It is not only because these two countries are neighbors geographically, but also because they were once a single country for a couple of years before Singapore was expelled from Malaysia in 1965.

Meanwhile, 2015 was an eventful year for Singapore. It celebrated the 50th anniversary of its independence, and with a slogan of "SG50", the nation was in a festive mood for the whole year. The passing of its founding father, Lee Kuan Yew, in March nevertheless cast a shadow on this festive spirit, and the General Election in September added even more craze.

I felt that such an unusual atmosphere heavily affected the discourse-making in Singapore. How did you see this moment?

Alfian: Nationalism definitely went into overdrive last year and it sometimes made our discourses quite monolithic and homogenous. There certainly was a sense that only particular kinds of ideas were allowed to be expressed openly in the public sphere. But I also think it was something of a godsend for the artists in Singapore, because many of us refused to be buoyed along this wave and it forced us to critically respond to certain issues like nostalgia, nationalism, and personality cults. Precisely because of these conditions, we got a lot of materials for counter and alternative discourses.

It was, however, an inexorable kind of wave that was sweeping almost the whole population and a lot of people demanded the silencing of dissenting voices. The land-slide victory of the ruling People's Action Party in the General Election contributed to this repressive atmosphere. There were victims of this kind of nationalistic, mythmaking process; documentary filmmaker Tan Pin Pin, whose film on Singaporean political exiles staying overseas was banned, was one of them.

―You yourself were involved in a controversy on the reevaluation of Lee Kuan Yew's legacy. Singapore's major daily, The Straits Times, quoted your Facebook post and put an article titled "Playwright Alfian Sa'at questions LKY legacy" on March 27th 2015, 4 days after his passing.

Alfian: Yes. It was an attempt to shut down any kind of critical views on Lee Kuan Yew. The thing is that the passing of a famous figure is both the best and the worst time to evaluate his legacy. It is the best time because you know that you have arrived at the conclusion of a life's record; the figure has no opportunity, for example, to revise his former positions or to apologize for past mistakes. It is also the worst time because in an atmosphere of public mourning, anything that strays from standard eulogy—which is to praise, not to criticize—can be shut down as "disrespectful."

So what happened was that censorship was imposed based on tone policing—"don't speak ill of the dead." There were no substantial arguments. Many of the people doing this policing were those who had not read alternative accounts of Lee Kuan Yew's ideologies and policies, so they could not engage in real debate. So they used what was at their disposal―emotional appeal―to shut down debates which used rational argument as a framework.

―Was that why you created the epic theater piece, HOTEL, with the local theater company W!LD RICE in 2015? It was commissioned by the Singapore International Festival of Arts and the production covered a hundred years of Singaporean history.

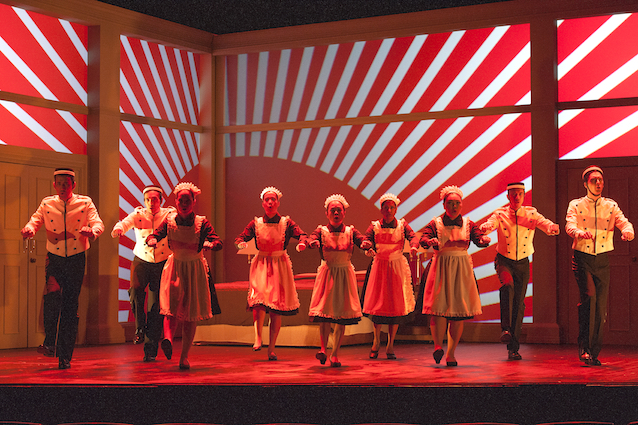

HOTEL (c)W!LD RICE

Alfian: Quite deliberately, HOTEL was a response to SG50. We wanted to ask, "what does it mean to talk only of the official history of SG50 when actually there are a lot of other histories, and some of them are still quite unresolved?" The creative team—co-directors Ivan Heng and Glen Goei, and co-writers Marcia Vanderstraaten and myself—felt that the SG50 narratives, which were constantly reproduced through television programs and documentaries throughout the year, were deficient. The timeframe, too, was artificial. I felt that even the idea of independence was stereotyped as it was always solely connected with what happened in 1965. This is problematic because, in fact, we actually had two stages of independence; first, we became independent from the British in 1963 as a part of Malaysia, and then, second, the expulsion of Singapore took place in 1965. Ours was not a typical story of a national struggle to achieve independence from colonizers. It came in stages without overt revolutionary violence, and the struggles were hidden and complex.

Although part one of HOTEL was set in the pre-independence era and part two was of the post-independence, the division was simply out of practicality as the show took five hours in total. For me, the story of the one hundred years in HOTEL is a continuous narrative and is not separated by the event of independence.

What was interesting and somehow strange at the same time was that many people actually bought tickets for part two without wanting to purchase part one. We were puzzled. Then we heard some people say, "Oh, well, you know, that this is more recent history so we think we can identify with it more." People were not very interested in the remote past and assumed that the recent past had more relevance to their lives.

―You mentioned that HOTEL was a response to the official narrative of SG50. Where did you try to position HOTEL in the numerous SG50-related discourses?

Alfian: I have always been interested in telling the human story and drama—I would call it the little people's history of Singapore. When we talk about history, it is usually about a great man's view. In Singapore, this has meant the grand narrative of Lee Kuan Yew.

Within myself, there has been a very conscious and deliberate desire to tell the history from the people's point of view, especially from the perspective of the people who have been marginalized. One example in Singapore today are the Eurasians, the people with mixed European and Asian parentage. There was even the Eurasians' exodus during the 1970s and '80s where a lot of them emigrated to Australia. The prime reason for this was the bilingual policy introduced by the government where each ethnic group was encouraged to speak both English and their own ethnic language. But the Eurasians did not fit into the official "Chinese, Malay, Indian" ethnic categorization and were labeled as "Others". It was a serious blow to their identity. They were not recognized as a group of people with a unique culture but were lumped together with all the other minority groups.

But obviously they were such a prominent part of Singapore's history, especially the colonial history, and Eurasians often occupied quite a privileged position in many countries and regions across Asia and Europe. They were like Mestizos and Mulattoes. They were nevertheless marginalized in modern Singapore, along with Peranakans, whose culture is a syncretic blend of Malay and Chinese cultures, simply because they do not fit the ways we see races here.

HOTEL (c)W!LD RICE