Farmers struggling for survival

I would submit that the crisis of farming and agriculture, and the retreat of the rural is a worldwide phenomenon. I would believe the crisis of the rural is as real in Japan as it is in India. It may have a different appearance. It may have different results. But there is a worldwide crisis of traditional agriculture, of family farming. And I believe, therefore, that the agrarian crisis, at least certainly in India, I would assert, has gone beyond the agrarian. It is now a societal crisis. Perhaps you can even describe it as a civilizational crisis, where the largest bodies of small landowning farmers in the world are struggling for survival.

Not only do I believe it is a civilizational crisis, but having covered the agrarian crisis in India since 1998 and continuing to do so, I begin to wonder if it is not a crisis of our own humanity, that we can stand by silently, while in India, 310 thousand farmers, official figure, 310 thousand farmers have committed suicide in 20 years. That's a figure from National Crime Records Bureau. Most of these farmers were driven by indebtedness. And indebtedness driven by economic policies that we consciously adopted as a nation. From early 1990s, India embarked on the brave new world of, what we are pleased to call economic reforms, but which was essentially an imposition of neo-liberal economics and neo-liberal economic policies on an unwilling population. These policies broadly were, in terms of the subject of major diversion of credit, of bank credit, of public credit, and public investment in agriculture, in terms of credit it was a diversion from agriculturalist to agri-business. So, instead of the farmers getting the amount of direct credit to farmers went down dramatically, while the amount of credit to corporations owning and controlling seed, fertilizer, pesticide, that rose dramatically. So we had a very major shift in transferring credit from the small landholding farmer, from the small farmer, to very large corporations. In the name of market based pricing, a free-market based pricing, and of course, as every one of you knows, there is no such thing as a free market. We allowed price-gouging by the corporations. So, the cost of each input in agriculture went up sometimes by several hundred percent. The cost of cultivation per acre in, say, cotton, which is the main crop where the suicides occur, not only one, but major, has gone up by several hundred percent. The cost of cultivation, the farmers' income has not kept pace with that. At that very moment when they need credit, you have diverted the credit to the corporations. So the farmers were hit, by one hand: lack of access to credit, on the other hand: exploding cost of cultivation. At the same time as the cost of cultivation went up, the price the farmers receive for their products collapsed, because we induced millions of subsistence farmers over 20 years to shift from producing food crop to producing cash crop. These farmers were then severely hit by the walletility of global prices in agricultural commodities, which are largely controlled by half a dozen corporations. Even as we speak, the other instruments of the market, "forward trading," futures, the trading in futures, this has devastated crop prices at local markets. So, farmers in the state I come from, Maharashtra, there's an area called Nashik, which is a very large producer of onions. When their harvest hits the market, the prices have fallen sometimes to two rupees for a kilogram. Two rupees for a kilogram. 200 miles away, that is 80 rupees a kilogram. There is a huge amount of speculation in the forward trading, in the futures, that is devastating the small farmer who has no control over these prices, has lost complete control over setting price for his product.

40 thousand farmers' protest

Now these problems are accompanied by a huge mega water crisis, which is also man-made problem, not just a problem of nature. The way we use and distribute water, and who controls water, what kind of crops we are growing in areas where there is less water, all these have added up to a gigantic water crisis in many aspects of which I don't have time to elaborate. Plus, we have a very serious soil fertility crisis, as the soil is losing its fertility, in region of the region, from overuse of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, and other chemicals.

Consequently, you have also got a gigantic employment crisis, and between 2001 and 2011, the largest migrations we have seen in India since the partition. If we take the two census documents, 1991 census of India, 2011 census of India, the next one is two years away, but in these twenty years, the population of fulltime farmers, has fallen by 15 million. So, where have they gone? Many of these have simply become agricultural laborers. They have fallen into to the agrarian underclass. Many others have migrated to other villages, to other towns, to other cities, in search of jobs, that are not there. In the last two years, there have been dramatic, large, and getting larger, farmers' protests all over the country. Last March, in March 2018, 40 thousands of the poorest farmers Adivasis, the tribal farmers from Nashik, the same Nashik of onions. 40 thousand of these farmers, men, women, children, women aged in their late sixties, grandmothers bringing along grandchildren, 40 thousand of them marched in their protest march from Nashik to Mumbai, 182 kilometers in 40 decrees heat. Most of these farmers are so poor they cannot afford and do not own footwear. They marched barefoot and arrived in Mumbai with their feet bleeding, cut-open. In November 29th and 30th, barely three months ago, a giant rally of farmers descended upon the national capital of Delhi. They came from 21 different states in the country.

People's Archive of Rural India- filling the gap between mas media and mas reality

I believe the media are trapped, you know, they are in the prism of their own making. The last thirty years has seen a serious corporatization of the media. The ownership of the media is in fewer and fewer ends, which are corporate-owned. And they have reduced journalism to a revenue stream-I will cover you if I make money out of it, if I do not make money out of covering you, I don't care for you. In conclusion, you can say that the Indian media, this is the paradox, the Indian media are politically free and imprisoned by profit. I also believe, worldwide, this phenomenon of corporatization means the fundamental feature of the media of our times is a growing disconnect between mass media and mass reality. India has thousands of young, very fine, highly sensitive journalists, who want to do this work, but cannot within the confines of their media, which is why many experiments have sprung up especially in the digital media. In 2014, my colleagues and I, all of whom had more than 35 years in the main media, started the People's Archive of Rural India, dedicated wholly to the daily lives of everyday people in the Indian subcontinent. It's only dedicated to rural India. But we cover rural migrants in urban India. But please do see. You can pick up a card from me of the People's Archive of Rural India, where you will get a sense of what's going on in the countryside. Thank you all very much.

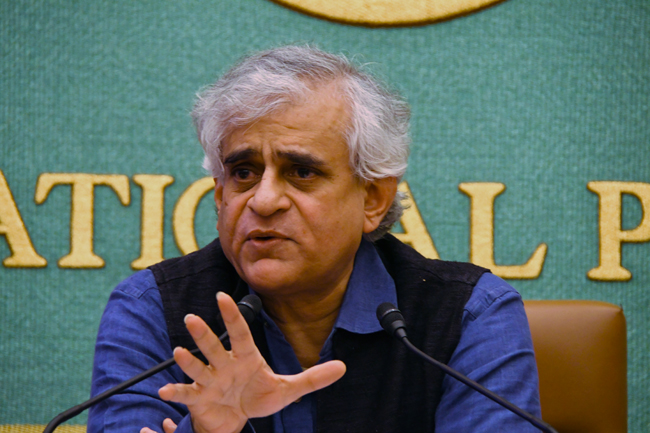

[On February 18, 2019 at the Japan National Press Club]

Mr. Palagummi Sainath' s talk at the Japan National Press Club.